In 2019 I bought the miniseries Oliver mainly because I love Darick Robertson as an artist, and even if I had no idea who the writer was, I already had a lot of interest in the title because I knew the art would be phenomenal. At the end of 2020 I saw the solicitation for Space Bastards, it sounded like a fun concept but, of course, what really sold me on the title was the fact that Robertson was in charge of the covers and the interior art.

The first chapter of “Tooth and Mail” (originally published in Space Bastards # 1, January 2021) is written by Eric Peterson and Joe Aubrey, two writers I wasn’t familiar with, but who are talented enough to be put on my to watch list. Interestingly, the publisher of Space Bastards is Humanoids, the same one that edits in the US the seminal works of Moebius and Jodorowski. So with such an auspicious pedigree I was delighted to dig into Space Bastards, and I certainly enjoyed the ride.

Peterson and Aubrey write about a future that, in my opinion, has echoes of some classic 2000 AD stories, but also some of the material published in Métal hurlant (Heavy Metal). The basic premise is that “In the future, unemployment and job dissatisfaction are sky-high. When you've got nothing left to lose, you join the Intergalactic Postal Service (IPS). Its postal fees are steep—and they go only to whomever ultimately fulfills the delivery, making every run a comically violent free-for-all between the most ruthless mercenaries in the cosmos”.

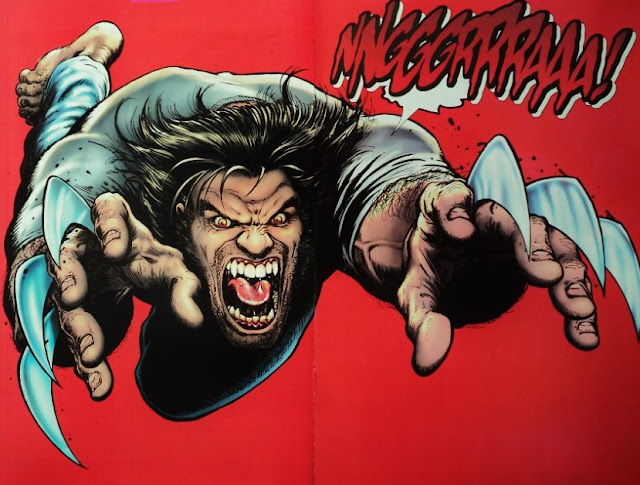

The main characters of the first chapter are David S. Proton and Manny Corns, a.k.a. 'The Manicorn'. Proton is described as a “meek, unemployed accountant desperate for money”, while Manny is a “sardonic brute who thrives on the competition provided by the IPS”. Two opposing characters that seem to have nothing in common and yet precisely because of their differences they’re hilarious together; however, does this mean they can work as partners for the IPS?

In the second chapter (Space Bastards # 2, February 2021) we learn more about the origins of this unusual job, which combines the delivering of a package with the maiming and killing of whoever gets in the way. The way it happened was that “years ago, after failing to make a profitable exit from his sex robot company, Roy Sharpton hit upon his next big idea: buy the failing Intergalactic Postal Service”. Roy will reinvent himself as the head of the IPS, and turns near bankruptcy into a very successful business model. It’s all about the money for Roy, and he cares little (or nothing at all) for the lives that are lost in the process.

In the third chapter (Space Bastards # 3, March 2021) we get to see what happens during Manny’s day off, certainly the Manicorn isn’t used to peacefully coexist with other people, and that becomes more than evident in the pages of this issue. Manny now hates David Proton, and soon the former accountant will need to enlist the aid of Mary Resurrection, whose ‘secret origin’ is explored in the fourth chapter (Space Bastards # 4, April 2021).

Like I said before, as soon as I saw Darick Robertson’s name I preordered Space Bastards. Robertson has become famous especially after his long run on Garth Ennis’ The Boys, in which sexual escapades, scandals and characters with unlimited libido spiced things up in the universe created by Ennis. Robertson did a fantastic job in all the scenes with a sexual component, and he does the same in the fifth chapter (Space Bastards # 5, May 2021).

Roy Sharpton organizes the annual party for the workers of the IPS: “for one day a year, the Intergalactic Postal Service shuts down for Sharptoberfest, a celebration so wild and debaucherous it could only be used to commemorate the birth of Roy Sharpton, Postmaster General & CEO of the IPS”. Thanks to Peterson and Aubrey I laughed out loud at all the over-the-top craziness that happens here, but none of it would’ve been so meaningful without Robertson’s art. One page after another, the talented American artist surprises us. I’m very glad I decided to read Space Bastards and I absolutely recommend it if you’re a fan of titles like The Boys.

________________________________________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________________________________________

El 2019 compré la miniserie Oliver principalmente porque amo a Darick Robertson como artista, e incluso si no tenía idea de quién era el escritor, ya tenía mucho interés en el título porque sabía que el arte sería fenomenal. A finales de 2020 vi la convocatoria de Space Bastards, sonaba como un concepto divertido pero, por supuesto, lo que realmente me convenció del título fue el hecho de que Robertson estaba a cargo de las portadas y el arte interior.

El primer capítulo de "Tooth and Mail" (publicado originalmente en Space Bastards # 1, enero de 2021) está escrito por Eric Peterson y Joe Aubrey, dos escritores con los que no estaba familiarizado, pero que tienen el talento suficiente para ponerme en mi lista de vigilancia. Curiosamente, el editor de Space Bastards es Humanoids, el mismo que edita en Estados Unidos las obras seminales de Moebius y Jodorowski. Entonces, con un pedigrí tan auspicioso, estaba encantado de profundizar en Space Bastards, y ciertamente disfruté el viaje.

Peterson y Aubrey escriben sobre un futuro que, en mi opinión, tiene ecos de algunas historias clásicas de 2000 d.C., pero también parte del material publicado en Métal hurlant (Heavy Metal). La premisa básica es que “En el futuro, el desempleo y la insatisfacción laboral están por las nubes. Cuando no tenga nada que perder, únase al Servicio Postal Intergaláctico (IPS). Sus tarifas postales son elevadas, y van solo a quien finalmente cumple la entrega, lo que hace que cada carrera sea un combates cómicamente violentos entre los mercenarios más despiadados del cosmos ”.

Los personajes principales del primer capítulo son David S. Proton y Manny Corns, también conocido como 'The Manicorn'. Proton es descrito como un "contador manso, desempleado y desesperado por dinero", mientras que Manny es un "bruto sardónico que se nutre de la competencia proporcionada por el IPS". Dos personajes opuestos que parecen no tener nada en común y, sin embargo, precisamente por sus diferencias, son divertidísimos juntos; sin embargo, ¿esto significa que pueden trabajar como socios del IPS?

En el segundo capítulo (Space Bastards # 2, febrero de 2021) aprendemos más sobre los orígenes de este trabajo inusual, que combina la entrega de un paquete con mutilar y matar a quien se interponga en el camino. La forma en que sucedió fue que “hace años, después de no lograr una salida rentable de su compañía de robots sexuales, Roy Sharpton tuvo su próxima gran idea: comprar el fallido Servicio Postal Intergaláctico”. Roy se reinventará a sí mismo como director del IPS y se convertirá al borde de la quiebra en un modelo de negocio muy exitoso. Todo se trata del dinero para Roy, y a él le importan poco (o nada) las vidas que se pierden en el proceso.

En el tercer capítulo (Space Bastards # 3, marzo de 2021) podemos ver qué sucede durante el día libre de Manny, ciertamente el Manicornio no está acostumbrado a convivir pacíficamente con otras personas, y eso se vuelve más que evidente en las páginas de este número. . Manny ahora odia a David Proton, y pronto el excontador deberá contar con la ayuda de Mary Resurrection, cuyo "origen secreto" se explora en el cuarto capítulo (Space Bastards # 4, abril de 2021).

Como dije antes, tan pronto como vi el nombre de Darick Robertson, reservé Space Bastards. Robertson se ha hecho famoso especialmente después de su larga carrera en The Boys, de Garth Ennis, en la que aventuras sexuales, escándalos y personajes con libido ilimitada condimentaron las cosas en el universo creado por Ennis. Robertson hizo un trabajo fantástico en todas las escenas con componente sexual, y lo mismo hace en el quinto capítulo (Space Bastards # 5, mayo de 2021).

Roy Sharpton organiza la fiesta anual para los trabajadores del IPS: “por un día al año, el Servicio Postal Intergaláctico cierra por Sharptoberfest, una celebración tan salvaje y libertina que solo podría usarse para conmemorar el nacimiento de Roy Sharpton, Director General de Correos & CEO del IPS ”. Gracias a Peterson y Aubrey, me reí a carcajadas de toda la locura exagerada que ocurre aquí, pero nada de eso hubiera sido tan significativo sin el arte de Robertson. Una página tras otra, el talentoso artista estadounidense nos sorprende. Estoy muy contento de haber decidido leer Space Bastards y lo recomiendo absolutamente si eres fanático de títulos como The Boys.