|

| Stephen Bissette & John Totleben |

After destroying a covenant of aquatic vampires, John Contantine asks Swamp Thing to embark on another adventure. This time, however, there are no evil creatures, just a woman scorned and humiliated by her sexist husband. Alan Moore explains the practices of the native American Indians and how they used to temporarily exile menstruating women. There is a stigma associated with the female condition and the blood of the reproductive cycle.

In the story, a husband makes fun of his wife, telling her that the Indians were smart enough to get rid off women during “that time of the month”. Moore presents a middle class couple and their middle class neighbors. Men joke around about pre-menstrual-syndrome and the infinite patience required to deal with that. Women simply set the table and clean the dishes. Have things changed after 28 years? I seriously doubt that. Men still feel more comfortable with machismo and women are still slightly discriminated in our phallocentric society. In most countries, including my own, women earn less money than men despite the fact of having the same educational background. Cases of domestic violence continue to arise, and it is still women who get injured at the hands of their husbands. Every TV ad about cleaning products keeps showing the same image: a docile housewife whose only purpose in life is to do the laundry. It’s amazing, and we’re supposed to be in the 21st century.

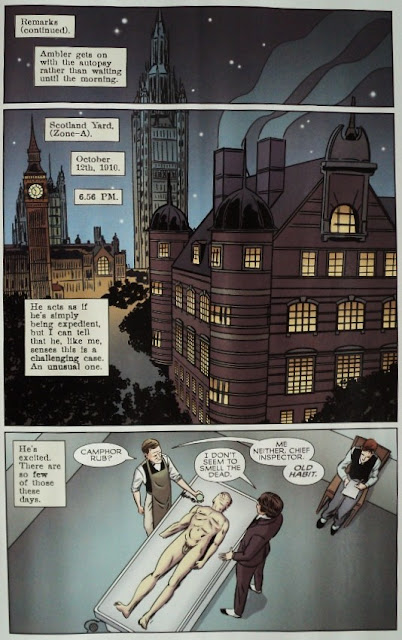

When “The Curse” was published in Swamp Thing # 40 (September 1985), many readers were scandalized by the story. Besides, the Comics Code Authority strictly forbade sex and all related subjects. Therefore menstruation was a taboo. Nevertheless, Karen Berger decided to publish the story anyway, and today, almost three decades later, it still remains as a justified admonition. Stephen Bissette and John Totleben drew some truly spectacular pages here, my favorite is probably the confrontation between Swamp Thing and the wolf-woman, the immobile and monstrous bodies before the struggle and the intricately detailed close up of the last two panels.

“Strange Fruit” has one of the best initial pages I have read in my life. The skeleton of a black slave, buried centuries ago, cannot rest. He wants to yawn but he’s afraid to lose his jaw in the process, he can’t raise his hand to “rub the cobwebs” from his eye sockets. He feels the formation of fungus for fifty years, he counts the insects that walk over his bones, he names them, one by one, inventing “dynasties” of bugs, he does everything he can, but eventually he realizes that it is impossible to sleep, and he starts moving. And next to him, in the coffins of the cemetery, all the dead awake, anxious, longing for freedom: “The pain cannot be buried and forgotten. The pain cannot remain in the past or hidden beneath the soil. That which is buried is not gone. That which is planted will grow”. The result of centuries of slavery is no longer buried, and the few white men that remain in the plantations will soon fall prey of an army of living dead. Swamp Thing manages to burn down most of the zombies, but a few of them escape. In the final page, one of them “finds coffin-like comfort working the ticket booth in a grindhouse theater”, coming from another era, he feels more than satisfied making minimal wage and having no benefits or rights, his employer knows that he’s exploiting this odd looking man, but he’s so happy about finding a hardworking man that will never complain about anything.

The penciler of “Strange Fruit” is Stephen Bissette, and his inker this time is Ron Randall. In the preface of this volume, Stephen explains that the last page of this issue made him realize something: “it still resonates with the reality of what I was living at the time. Unlike the zombie ticket seller I wasn’t happy feeling boxed in” and so after two years of non-stop work Stephen finally decided that it was time to take a rest. He would only stay until the end of the American Gothic saga. And thus begins the end of an era.

________________________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________________________

|

| Against a wolf-woman / contra la mujer lobo |

La licantropía está asociada a los ciclos lunares. La luna llena exacerba a la bestia interior. Pero ¿qué sucede cuando, en vez de un hombre lobo tradicional, tenemos a una mujer lobo? ¿El ciclo lunar la estimula de la misma manera? ¿O su transformación bestial es afectada por el ciclo de la menstruación?

Después de destruir a un clan de vampiros acuáticos, John Contantine le pide a Swamp Thing que se embarque en otra aventura. Esta vez, sin embargo, no hay criaturas malignas, sólo una mujer denigrada y humillada por su esposo machista. Alan Moore explica las prácticas de los indios norteamericanos nativos y cómo solían exiliar temporalmente a las mujeres cuando menstruaban. Hay un estigma asociado con la condición femenina y la sangre del ciclo reproductivo.

En la historia, un marido se burla de su esposa, diciéndole que los indios tenían la astucia suficiente para deshacerse de sus mujeres durante "ese periodo del mes". Moore presenta a una pareja de clase media y a sus vecinos de clase media. Los hombres bromean sobre el síndrome pre-menstrual y la infinita paciencia requerida para lidiar con esto. Las mujeres simplemente ponen la mesa y lavan los platos. ¿Han cambiado las cosas después de 28 años? Realmente lo dudo. Los hombres todavía se sienten más cómodos el machismo y las mujeres son levemente discriminadas en nuestra sociedad falocéntrica. En la mayoría de países, incluyendo el mío, las mujeres ganan menos que los hombres a pesar de contar con el mismo nivel educativo. Los casos de violencia doméstica continúan aumentando, y todavía son las mujeres las que son golpeadas por sus esposos. Todos los comerciales de televisión sobre productos de limpieza siguen mostrando la misma imagen: una ama de casa dócil cuyo único propósito en la vida es lavar la ropa. Es asombroso, y se supone que estamos en el siglo XXI.

|

| Stephen Bissette & Alfredo Alcalá |

Cuando “La maldición” fue publicada en Swamp Thing # 40 (setiembre de 1985), mucho lectores se escandalizaron. Además, la Autoridad del Código de los Cómics prohibía estricta-mente el sexo y todo tema sexual. La menstruación era un tabú. No obstante, Karen Berger decidió publicar la historia de todos modos, y hoy en día, casi tres décadas después, sigue siendo una denuncia justificada. Stephen Bissette y John Totleben dibujan algunas páginas realmente espectaculares, mi favorita es probablemente la confrontación entre Swamp Thing y la mujer-lobo, los cuerpos monstruosos e inmóviles antes de la lucha y el acercamiento detallado en los últimos dos paneles.

|

| night of the living dead / la noche de los muertos vivientes |

Me gustaría decir que después de 30 años el racismo no existe. Pero, por supuesto, si dijera eso estaría mintiendo. "Cambio sureño" (Swamp Thing # 41) empieza con la inofensiva llegada de unos productores de televisión. Están filmando una nueva telenovela en las plantaciones de Louisiana. Los lugareños han sido contratados como extras e incluso Abby Arcane visita el set. Sin embargo, la presencia de los vivos perturba en gran medida a los muertos: "¿En qué piensan, en sus lechos bajo tierra? ¿En qué piensan los muertos?". Seguramente recuerdan... cientos de esclavos negros, torturados, mutilados, asesinados, piensan en sus amos blancos. Cuando Abby habla sobre la ironía de tener a los descendientes de esclavos negros actuando como esclavos negros en un show de televisón sólo para recibir un mísero cheque, ella le pregunta a Swamp Thing si eso es triste o chistoso. "Es humano" es su respuesta. El artista es de nuevo Stephen Bissette, pero como John Totleben estaba ocupado produciendo una hermosa portada pintada, el entintador invitado es Alfredo Alcalá. Alfredo provee una muy necesaria fuerza y rudeza a los lápices del artista, expresando así toda la ira y el odio entre negros y blancos.

|

| the revenge of the black slaves / la venganza de los esclavos negros |

|

| Strange Fruit / Fruto extraño |

Los lápices de “Fruto extraño” son de Stephen Bissette, y las tintas esta vez son de Ron Randall. En el prefacio de este volumen, Stephen explica que la última página de este número lo hizo darse cuenta de algo: "todavía resuena con la realidad de lo que estaba viviendo en ese momento. A diferencia del zombi de la taquilla, yo no era feliz sintiéndome encasillado" y así, después de dos años de trabajo sin parar, Stephen finalmente decidió que era hora de descansar. Sólo se quedaría hasta el final de la saga American Gothic. Y de este modo empieza el fin de una era.