|

| Stephen R. Bissette & John Totleben |

Chester, a jobless hippy who sells marijuana to his loyal customers, becomes the focal point of this amoral tale. The rest of the characters converge around him, attracted by his latest discovery: a fruit produced by the body of Swamp Thing. He shares the fruit with two men. The first man gives it to his wife, who’s dying of cancer, and through a psychedelic dream the couple rediscovers the value of life and the beauty of nature: “We spend our lives, pressing our bodies against each other, trying to break the surface tension of our skins, to unite in a single bead”. The dying woman embraces life more than ever, and through an orgasmic and cosmic experience she bonds with his husband in ways none of them could have imagined before. The second man eats the fruit and sees himself as a monster; plagued by nightmares and horrible visions, he goes mad. He dies only minutes after eating the mysterious fruit.

Chester hears what happened to his ‘customers’. The first one is happy and grateful; the second one, dead. If the fruit somehow brings to the surface who we are, our true essence, then it means that we can either have a good or a bad trip… and the consequences of the bad trip can be deadly. The last page is my favorite. Chester stares at the last piece of fruit, trying to decide if he’s a good or a bad person, trying to speculate what could happen to him if he ingested the fruit. In the end, indecision overwhelms him. He won’t eat it, but then again, would you?

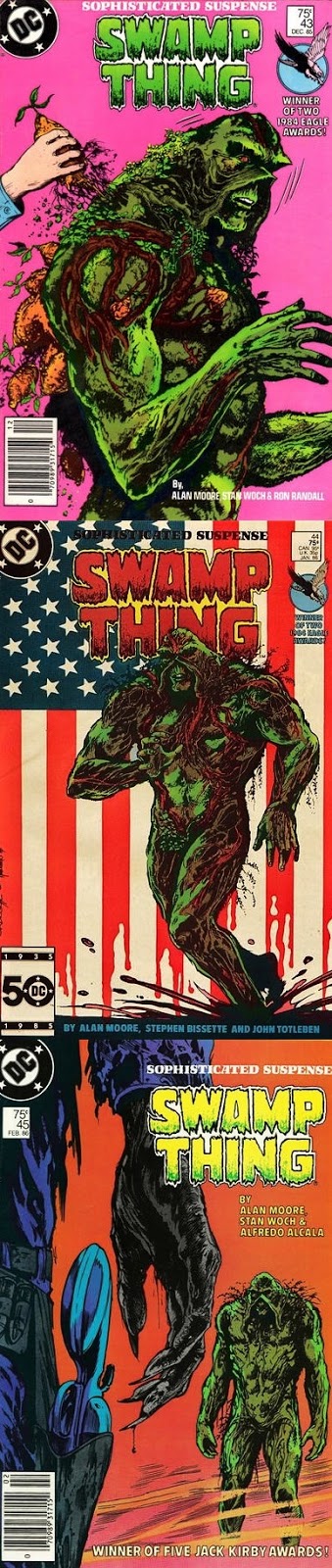

Penciler Stan Woch and inker Ron Randall take advantage of the hallucination provoked by the fruit and create highly imaginative sequences and an indisputable oneiric beauty; as usual, Tatjana Wood’s colors are superb.

In the “Bogeymen” (January 1986), a serial killer obsessed with the eyes of his victims goes through the swamps of Louisiana. This is a man that has killed 165 people, and has memorized their eyes. He can remember the eyes of all his victims and he often rejoices in this macabre remembrance. The world is agitated. Madness is stirring inside the Bogeyman’s head, and all around the world, the sky has turned red.

The Crisis on Infinite Earths is upon us, and the red skies are a warning of what is to come, and that’s what Batman says when he runs into John Constantine and Steve Dayton (formerly known as Mento, the hero with mental powers) in a short but very memorable sequence… seeing Batman taking a few minutes to recognize Mento is just priceless.

Stephen Bissette, Ron Randall and John Totleben magnificently illustrate “Bogeymen”: their detailed lines and intricate designs mesmerize the readers, but it’s the balance between shadows and light that surprises us the most. The final splash page is one of the most beautiful compositions we’ve seen in this title so far, and that’s saying a lot. The face of Swamp Thing is hidden in the darkness of the night, his left eye is there for us to see and his right eye is replaced by the shining midnight moon, and below all of this, the creature of the swamp walks into the woods, into the dark. What a fantastic page. I still remember when I read this story for the first time. Having Swamp Thing materializing in Abigail’s bathroom sure was a scary moment, and it works perfectly thanks to the artistic team.

|

| Sex: an antidote against death? / el sexo: un antídoto contra la muerte |

Ever since the opening salvo of “American Gothic”, Alan Moore reimagined some of the most traditional troupes of the horror genre. Vampires were turned into subaquatic creatures in Rosewood lake; the myth of the werewolf was transformed into an allegory of machismo, the subjugation of women and the lunar phases replaced by the menstrual cycle. Now Moore plays with the classic haunted house, filling the empty figure of the ghost with social criticism.

Bang, bang! Surely we’ve heard that onomatopoeia before, and Alan Moore plays with it. On the one hand, the bang-bang makes references to revolver shots, but also the sound of hammering. In “Ghost Dance” (February 1986) both elements are combined into one enthralling narrative. A wealthy family has built a house over six acres of their property. Such monumental construction demanded the constant work of men, and thus the sound of hammers and nails were heard for years. Until it all stopped. And once it stopped a very familiar sound reappeared. The sound of guns. Every man, woman or child –even animals– murdered by the bullet of a Cambridge gun reappear as ghosts inside the gigantic house. And when a group of friends visit the house, all the ghosts reawaken.

This isn’t a politically correct story. Alan Moore challenges the hegemony of groups such as the National Rifle Association (we know that the people who enter the house have ties with that organization), and that’s what’s so great about it. Because the main idea here isn’t a pretty one: America was built on the corpses of Indians, much in the same way that this house was built thanks to the opulence generated by the production and commercialization of the Cambridge repeater (a cheaper version of the Winchester rifle). A hammer against a nail, a bullet against our flesh, it’s all the same. But the sound must stop. And Swamp Thing knows how to stop it.

|

| While Abigail reads a Clive Barker novel something strange happens in the bathroom / Mientras Abigail lee una novela de Clive Barker algo extraño sucede en el baño |

The art here is in the hands of Stan Woch and Alfredo Alcalá, and they create a dark and ominous atmosphere. They recreate the horror of death but above all the horrific fascination Americans have always felt towards weapons. At the end, John Constantine reappears and congratulates Swamp Thing, but he also highlights how close they are to the end: “I’ve got a couple of front row tickets for the end of the universe”. Now that’s something that deserves to be seen.

________________________________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________________________________

|

| Batman, Steve Dayton (Mento) & John Constantine |

Durante décadas, las drogas fueron uno de los muchos tabús intocados -e intocables- de los cómics de difusión masiva de Estados Unidos. Pero el consumo de drogas no era algo ajeno para Alan Moore (después de todo, cuando era adolescente, fue expulsado de su colegio a causa de un altercado que involucraba drogas). Ocasionalmente, DC y Marvel habían mencionado el tema de las drogas, siempre enfocándose en los aspectos negativos de la adicción y en las consecuencias letales de ingerir sustancias ilegales. Así que me sorprende ver que "Fruto del cielo" (publicado en Swamp Thing # 43, diciembre de 1985) fuera aprobado en primer lugar. Después de todo, aquí las drogas no sólo son el camino al infierno, también son la escalera al cielo. Supongo que se lo debemos a la audacia de la editora Karen Berger.

Chester, un hippy desempleado que les vende marihuana a sus leales clientes, se convierte en el punto focal de este relato amoral. El resto de los personajes convergen alrededor de él, atraídos por su más reciente descubrimiento: un fruto producido por el cuerpo de la Cosa del Pantano. Él comparte el fruto con dos hombres. El primero se lo da a su esposa, que está muriendo de cáncer, y a través de un sueño psicodélico la pareja redescubre el valor de la vida y la belleza de la naturaleza: "Vivimos nuestras vidas presionando nuestros cuerpos entre sí, intentando quebrar la tensión en la superficie de nuestras pieles, para unirnos en una sola gota". La mujer moribunda abraza la vida más que nunca, y a través de una experiencia orgásmica y cósmica, se une a su marido en modos que nadie podría haber imaginado antes. El segundo hombre come el fruto y se ve a sí mismo como un monstruo; enloquece plagado por pesadillas y horribles visiones. Muere apenas unos minutos después de comer el misterioso fruto.

|

| Extraordinary composition by Bissette & Totleben / Extraordinaria composición de Bissette y Totleben |

Chester escucha lo que les pasa a sus 'clientes'. El primero está feliz y agradecido; el segundo, muerto. Si la fruta de algún modo trae a la superficie quiénes somos, nuestra verdadera esencia, entonces eso significa que podemos tener un buen o un mal viaje... y las consecuencias del mal viaje pueden ser mortales. La última página es mi favorita. Chester se queda mirando el último pedazo del fruto, intentando decidir si es una buena o mala persona, intentando especular qué podría pasarle si es que ingiere el fruto. Al final, la indecisión lo abruma. No se lo come, pero, ¿acaso ustedes sí se lo comerían?

Los artistas Stan Woch y Ron Randall aprovechan la alucinación provocada por el fruto y crean secuencias sumamente imaginativas y de una indiscutible belleza onírica; como siempre, los colores de Tatjana Wood están soberbios.

En “El hombre del saco” (enero 1986), un asesino en serie obsesionado con los ojos de sus víctimas atraviesa los pantanos de Louisiana. Este es un hombre que ha matado a 165 personas, y ha memorizado sus ojos. Puede recordar los ojos de todas sus víctimas y a menudo se regodea en esta remembranza macabra. El mundo está agitado. La locura se arremolina en la cabeza del hombre del saco, y a lo largo del mundo, el cielo se ha vuelto rojo.

La Crisis en Tierras Infinitas ha llegado, y los cielos rojos son una advertencia de lo que pasará, y eso es lo que dice Batman cuando se encuentra con John Constantine y Steve Dayton (antiguamente conocido como Mento, el héroe con poderes mentales) en una corta pero muy memorable escena... Ver a Batman demorándose algunos minutos en reconocer a Mento no tiene precio.

|

| Alan Moore reinvents the haunted house / Alan Moore reinventa la casa embrujada |

Stephen Bissette, Ron Randall y John Totleben ilustran magníficamente “El hombre del saco”: sus líneas detalladas e intrincados diseños hipnotizan al lector, pero lo que más nos sorprende es el balance entre sombras y luz. La página final es una de las más bellas composiciones que hemos visto en la colección, y eso ya es decir bastante. El rostro de la Cosa del Pantano se oculta en la negrura de la noche, el ojo izquierdo está a la vista y el derecho es reemplazado por la resplandeciente luna de la medianoche, y debajo de todo, la criatura del pantano camina hacia los bosques, hacia lo oscuro. Una página fantástica. Todavía me acuerdo cuando leí esta historia por primera vez. Cuando la Cosa del Pantano se materializa en el baño de Abigail es un momento de miedo, y funciona perfectamente gracias al equipo artístico.

Desde el inicio de “American Gothic”, Alan Moore reinventó a la muchedumbre más tradicional del género del terror. Los vampiros fueron convertidos en criaturas subacuáticas en el lago Rosewood; el mito del hombre lobo fue transformado en una alegoría del machismo, la subyugación de la mujer y las fases lunares reemplazadas por el ciclo menstrual. Ahora Moore juega con la clásica casa embrujada, llenando de crítica social la vacía figura del fantasma.

¡Bang, bang! Seguramente hemos oído esta onomatopeya antes, y Alan Moore juega con ella. Por un lado, el bang-bang hace referencia al disparo del revólver, pero también al sonido del martilleo. En "Danza fantasma" (febrero 1986) ambos elemenos se combinan en una narrativa cautivante. Una familia acaudalada ha construido una casa sobre seis acres de su propiedad. Una construcción tan monumental ha demandado un trabajo constante, y así, el sonido de los martillos y los clavos fue escuchado por años. Hasta que todo se detuvo. Y una vez que se detuvo reapareció un sonido muy familiar. El sonido de las pistolas. Todo hombre, mujer o niño -incluso animales- asesinado por la bala de las armas Cambridge reaparece como fantasma dentro de la gigantesca casa. Y cuando un grupo de amigos visitan la casa, todos los fantasmas despiertan.

Esta no es una historia políticamente correcta. Alan Moore desafía la hegemonía de grupos como la Asociación Nacional del Rifle (sabemos que la gente que entra en la casa tiene vínculos con esta organización) y eso es lo que cuenta. Porque aquí la idea principal no es algo agradable: Estados Unidos se construyó sobre los cadáveres de los indios, del mismo modo que la casa se construyó gracias a la opulencia generada por la producción y comercialización del rifle Cambridge (una versión más barata del rifle Winchester). Un martillo contra un clavo, una bala contra nuestra carne, todo es lo mismo. Pero el sonido debe parar. Y la Cosa del Pantano sabe qué hacer para lograrlo.

Aquí el arte está en las manos de Stan Woch y Alfredo Alcalá, y crean una atmósfera ominosa y oscura. Ellos recrean el horror de la muerte y, por encima de todo, la horrenda fascinación que los estadounidenses sienten hacia las armas. Al final, John Constantine reaparece y felicita a la Cosa del Pantano, pero también subraya lo cerca que están del fin: "Tengo un par de boletos de primera fila para el fin del universo". Y eso es algo que merece verse.