I have already discussed the importance of ecology in Swamp Thing or the criticism towards a society plagued by racism. After 30 years, we’re finally accepting how essential ecology is and we’re still struggling against racist behaviors that, at least in theory, should’ve disappeared long ago. But there is something else in Alan Moore’s unforgettable run in Swamp Thing: the women problematic. There’s no need for us to be feminists in order to realize that even after 30 years women are still victims of abuse, discrimination and unfair treatment. Yes, theoretically, women and men have the same rights. But if you read the statistics you will still find thousands of cases of domestic violence, of men hurting women, here, there and anywhere in the world. It’s sad but it’s true.

Perhaps that’s one of the elements that I was never able to overlook when I first read “The Flowers of Romance” (published in Swamp Thing # 54, November 1986). Moore explores the subject of a woman constantly abused by her husband, to the point that she has turned into an infrahuman creature, unable to take care of herself, and with such low self-esteem that she no longer has the courage to make any decisions at all. And the most horrific part? This was actually based on a real life case: Alan Moore explains that his aunt suffered this dehumanization process at the hands of a viciously aggressive man and the family only found out about this when it was late.

“The Flowers of Romance” then, focuses on this disgraced woman, Liz Tremayne, and his abusive and brutal husband, Dennis Barclay. In case some might have forgotten about the couple, they were originally introduced during Martin Pasko’s previous run on the title, and they were briefly featured in “Loose Ends”, Alan Moore’s first historical issue.

Ironically, these loose ends are finally tied up when Liz finds Abby and asks her for help; and Dennis, an enraged maniac, decides to kill both women. After a vicious persecution, Dennis dies. Abby and Liz then prepare to travel to Gotham City, to attend the Swamp Thing’s funeral in “Earth to Earth” (Swamp Thing # 55).

“If you wear black, then kindly, irritating strangers will touch your arm consolingly and inform you that the world keeps on turning. They’re right. It does. However much you beg it to stop”, that’s how Abby begins this chronicle, affirming that we wrap “ourselves in comforting banalities to keep us warm against the cold”. However, after the initial pain of death, she somehow manages to come to terms with her loss. It’s not an easy task, but she is, after all, a survivor.

“My Blue Heaven” is a one of kind insight into the mind of those who have the power to create. Swamp Thing, unable to regrow his body in the solar system, has left his consciousness wander around the cosmos. Now, in a strange and blue planet, he reconstructs himself and he stares desperately at the loneliness of a world in which only the most primitive life forms thrive.

In his brilliant introduction, Stephen Bissette further elucidates the parallelisms between the ability to create and the self-congratulatory drive: “It’s arguably autobiographical in many ways […] The story begins as an ethereal and loving celebration of a creator (Swamp Thing/Alan) finding solace and temporary fulfillment in the act of creation/re-creation. The darkness –the loneliness, the masturbatory nature of such creation, the assertion of the shadowy realms of the creator’s unconsciousness– soon unveils the madness the creator knows and fears”. Indeed, “My Blue Heaven” is a poignant philosophical examination of a question more creators should be willing to ask, either about themselves or their works. And, at the same time, it’s a nightmare, a horrifying experience that almost costs Swamp Thing his sanity.

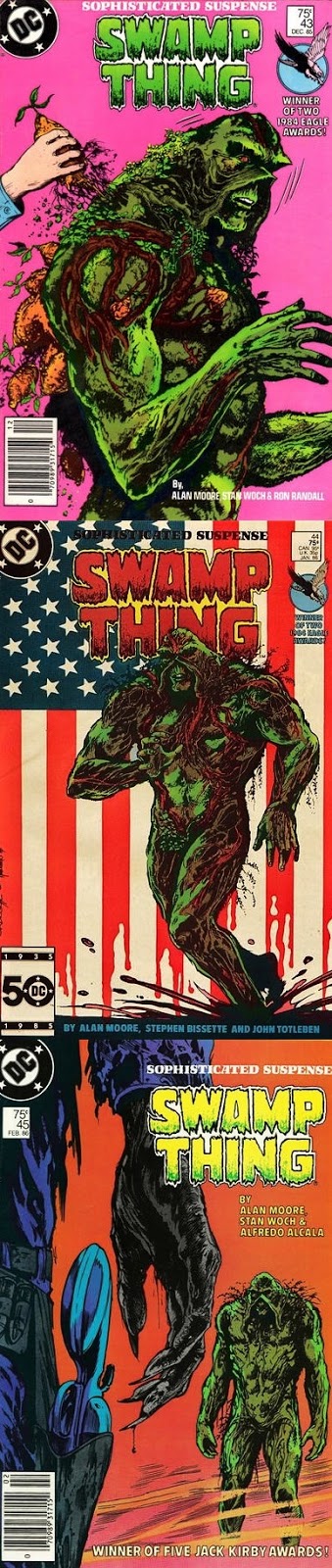

|

| John Totleben |

This extraordinary stand-alone adventure is illustrated by Rick Veitch: “Rick’s roots in the underground comix movement of the early 1970s occasionally erupts into some truly baroque visions of monstrous beauty, rendered with a ferocity and clarity precious few of his mainstream 1980s peers could approach”. Alfredo Alcalá, the inker, “grounds the fantasy of the imagery in a tactile and believable sense of ‘reality’” thanks to his “textural precision and atmospheric style”.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________

_________________________________________________________________________________________________

|

| Abby & Swamp Thing |

He escrito algunas historias e incluso unas pocas han sido publicadas, y a menudo me pregunto si serán leídas en el futuro... o al menos recordadas. Como escritores, enfrentamos un reto que desafía las normas de la narrativa o las distinciones de la puntuación. Hablo, desde luego, de la relevancia de nuestro trabajo, no sólo para los lectores de hoy sino también para aquellos que encuentren nuestra obra dentro de 10 o 100 años. Alan Moore es un escritor que puede ser considerado inmortal, no sólo por su asombrosa imaginación y su innegable talento, sino también porque cuando escribió sus historias parecía haber considerado tanto al lector del presente como al del futuro.

|

| Abby, Commissioner Gordon, Liz Tremayne & Batman |

Ya he discutido la importancia de la ecología en "Swamp Thing" o la crítica hacia una sociedad plagada de racismo. 30 años después, finalmente estamos aceptando que lo ecológico es esencial y todavía estamos luchando contra las conductas racistas que, al menos en teoría, deberían haber desaparecido hace mucho. Pero hay algo más en la inolvidable etapa de Alan Moore en "Swamp Thing": la problemática de la mujer. No hace falta ser feminista para darse cuenta que incluso después de 30 años las mujeres siguen siendo víctimas de abuso, discriminación y tratamientos injustos. Sí, teóricamente, las mujeres y los hombres tienen los mismos derechos. Pero si leen las estadísticas todavía podrán encontrar miles de casos de violencia doméstica, de hombres haciéndoles daño a mujeres, aquí o en cualquier otra parte del mundo. Es triste pero es verdad.

Tal vez ese es uno de los elementos que nunca fui capaz de relegar cuando leí por primera vez “Las flores del romance” (publicado en Swamp Thing # 54, noviembre de 1986). Moore explora el tema de una mujer constantemente abusada por su marido, al punto que se convierte en una criatura infrahumana, incapaz de cuidarse a sí misma, y con una autoestima tan baja que ya no tiene la valentía de tomar decisiones por sí misma. ¿Y lo más terrorífico? Esto se basó en un caso de la vida real: Alan Moore explica que su tía sufrió un proceso de deshumanización a manos de un hombre viciosamente agresivo y la familia sólo se enteró de esto cuando era demasiado tarde.

“Las flores del romance”, entonces, se enfoca en una desgraciada mujer, Liz Tremayne, y su abusivo y brutal esposo, Dennis Barclay. En caso que algunos se hayan olvidado de la pareja, su origen data de la etapa de Martin Pasko, y aparecieron brevemente en “Cabos sueltos”, el primer número histórico de Alan Moore.

|

| Blue planet / el planeta azul |

Irónicamente, estos cabos sueltos son finalmente atados cuando Liz encuentra a Abby y le pide ayuda; y Dennis, un maníaco rabioso, decide matar a ambas mujeres. Después de una feroz persecución, Dennis muere. Abby y Liz, entonces, se preparan para viajar a Gotham City, para asistir al funeral de Swamp Thing en “Tierra a Tierra” (Swamp Thing # 55).

“Si vistes de negro, entonces gente extraña te tocará el brazo, amablemente, consoladoramente, y te informarán que el mundo sigue girando. Tienen razón. Así es. Por más que ruegues que se detenga”, así es como Abby empieza esta crónica, afirmando que nos envolvemos “en banalidades cómodas para mantenernos tibios frente al frío”. Sin embargo, después del dolor inicial de la muerte, ella se las arregla para aceptar la pérdida. No es una tarea fácil pero ella es, después de todo, una superviviente.

“Mi cielo azul” es una mirada única a la mente de aquellos que tienen el poder de crear. La Cosa del pantano, incapaz de rebrotar su cuerpo en el sistema solar, ha dejado que su conciencia vague por el cosmos. Ahora, en un extraño planeta azul, se reconstruye a sí mismo y mira con desesperación la soledad de un mundo en el que sólo subsisten formas de vida primitivas.

En su brillante introducción, Stephen Bissette indaga sobre los paralelismos entre la habilidad para crear y el impulso de autosatisfacción: “Es probablemente autobiográfico de muchos modos […] La historia empieza como una celebración etérea y amorosa de un creador (Swamp Thing/Alan) que encuentra solaz y satisfacción temporal en el acto de la creación/re-creación. La oscuridad –la soledad, la naturaleza masturbatoria de semejante creación, la aserción de los reinos de sombras del inconsciente del creador– pronto revela la locura que el creador conoce y teme”. De hecho, “Mi cielo azul” es una importante examinación filosófica sobre una pregunta que más creadores deberían estar dispuestos a formular, ya sea sobre sí mismos o sus trabajos. Y, al mismo tiempo, es una pesadilla, una terrorífica experiencia que casi le cuesta a la Cosa del pantano su cordura.

Esta extraordinaria aventura auto-conclusiva es ilustrada por Rick Veitch: “Las raíces de Rick en el movimiento de comix underground de inicios de 1970 ocasionalmente estallan en visiones realmente barrocas de belleza monstruosa, retratadas con una ferocidad y una claridad a la que muy pocos de sus colegas de 1980 podrían haberse acercado”. Alfredo Alcalá, el entintador, “asienta la fantasía de las imágenes en un sentido táctil y creíble de ‘realidad’” gracias a su “precisión de texturas y su estilo atmosférico”.