It has taken Barry Windsor-Smith a considerable amount of years to conceive and create his magnum opus, Monsters, a masterpiece unlike anything I’ve seen before and one that has arrived at the right time. When I first started this blog, over a decade ago, I was impatient to review one of the best comic book runs ever: Conan the Barbarian by Roy Thomas and Barry Windsor-Smith. I did review every Conan issue illustrated by the talented British artist and I enjoyed the experience of re-reading all of it. Seeing the evolution of Windsor-Smith in the pages of Conan was like seeing a combination of comic book trends as well as a history of western art, entire centuries condensed in a month or two. Adopting multiple styles, and refining his technique, Windsor-Smith very quickly became the best artist of the 70s.

Monsters is the result of everything Barry Windsor-Smith has learned in his long and fruitful career. In the past, I would often imagine the British artist finding inspiration in Rembrandt, Goya, El Greco or even Auguste Rodin. For Neil Gaiman, however, the most important influence is that of the Renaissance and the Mannerism, and certainly I can easily perceive the influence of the work of geniuses such as Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo Buonarroti, Raffaello Sanzio, Sandro Botticelli, Donatello and Benvenuto Cellini. Sometimes a Windsor-Smith page can be evocative of Leonardo’s red chalk drawings or Raffaello’s engravings.

Furthermore, in his late Conan period, Windsor-Smith’s artwork reminded me of the ink drawings by Albrecht Dürer as well as his silverpoint illustrations, and his naturalistic setting were also a homage to the paintings of Hieronymus Bosch. Throughout all these pages, however, one constant remains: beauty, or rather, as Schilling used to call it, a sublime pathos that takes aesthetic concepts to a whole new level. No other artist in the history of comics, with the exception perhaps of Hal Foster and Frank Frazetta, and some of Windsor-Smith’s disciples, has conjugated so masterfully the artistic history of our civilization, and no one else has been able to balance all of this with dynamism, vibrant rhythm and unique pacing of the comic book medium. To say that Barry Windsor-Smith is simply an artist would never be enough because he is The Artist; he is all the artists that have existed before, and all the unending possibilities of art under the dominion of one lucid mind and two extremely capable hands.

|

| 1950: Bobby Bailey & Mrs. Bailey |

Once again, Barry Windsor-Smith synthetizes the history of western art, and so after the Renaissance and the Mannerism, we also have elements influenced by Baroque and Romantic periods. And intense pages that are similar to the works of Caravaggio. As the decades went by, Barry Windsor-Smith has fully embraced the Expressionist movement, and instead of an Albrecht Dürer working for Marvel, he was more like a Francis Bacon returning to the House of Ideas (for Michael Zulli, for instance, this is Windsor-Smith’s more interesting period). Artistic evolution, after all, is the key to understand the career of this incomparable British artist.

In Monsters, Windsor-Smith finds the equilibrium that so many strive for and very few ever achieve. He retains the best of his Renaissance and Mannerist influences, while also preserving the aspects that best serve to graphic storytelling, those aspects acquired during his more Expressionistic days. The result is an absolutely beautiful work of art. 360 pages that continued to leave me in awe and completely take my breath away. I thought about analyzing every single page of this original graphic novel, but I honestly don’t think it would be practical to have a review of almost 400 pages. Suffice it to say, I was absolutely fascinated by the art here. This is also the best black and white art I’ve seen in the 21st century, I don’t think anything else could compare to it. Every time I see something in black and white I always feel like the color is missing, here is the first time I’ve felt as if the color would get in the way. The way Windsor-Smith uses contrast, light and shadow, depth and perspective, would make color redundant here.

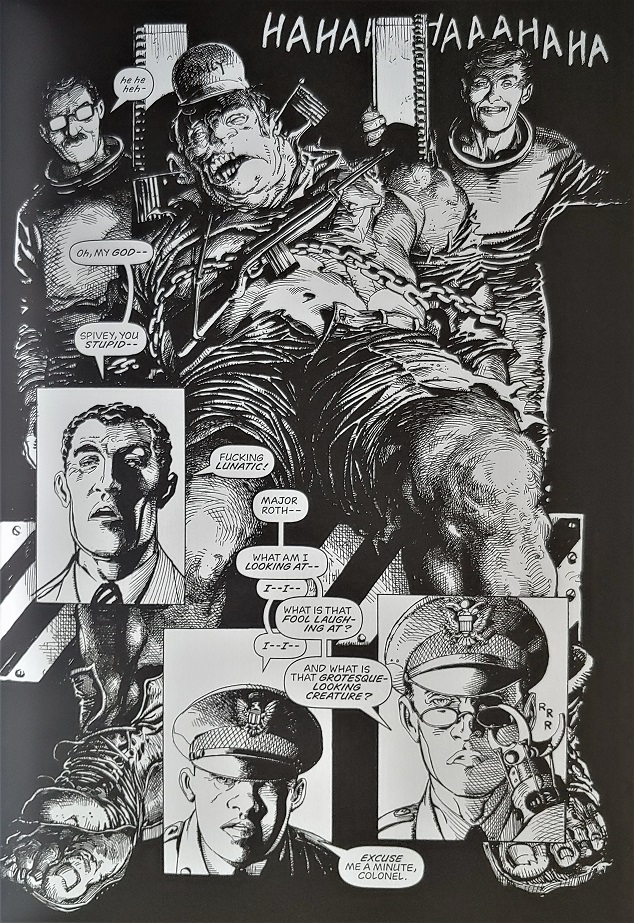

So far I’ve only talked about Barry Windsor-Smith the artist, but now it’s time I talk about Barry Windsor-Smith the writer. Few times in my life I’ve read a more intelligent, well-crafted, complex, multifaceted, engaging and captivating script as the one from Monsters. I had already expressed my admiration for Windsor-Smith as a full author, when he did Weapon X, but Monsters is much better: “in 1964, Bobby Bailey is recruited for a U.S. military experimental genetics program that was discovered in Nazi Germany 20 years prior. His only ally, Sergeant McFarland, intervenes to try to protect him, which sets off a chain of events that spin out of everyone’s control. As the titular monsters multiply, becoming real and metaphorical, literal and ironic, the story reaches its emotional and moral reckoning”. For many, this might seem like a typical comic book trope, genetic experimentation and Nazis, but in reality is so much more. Because this is barely the tip of the iceberg.

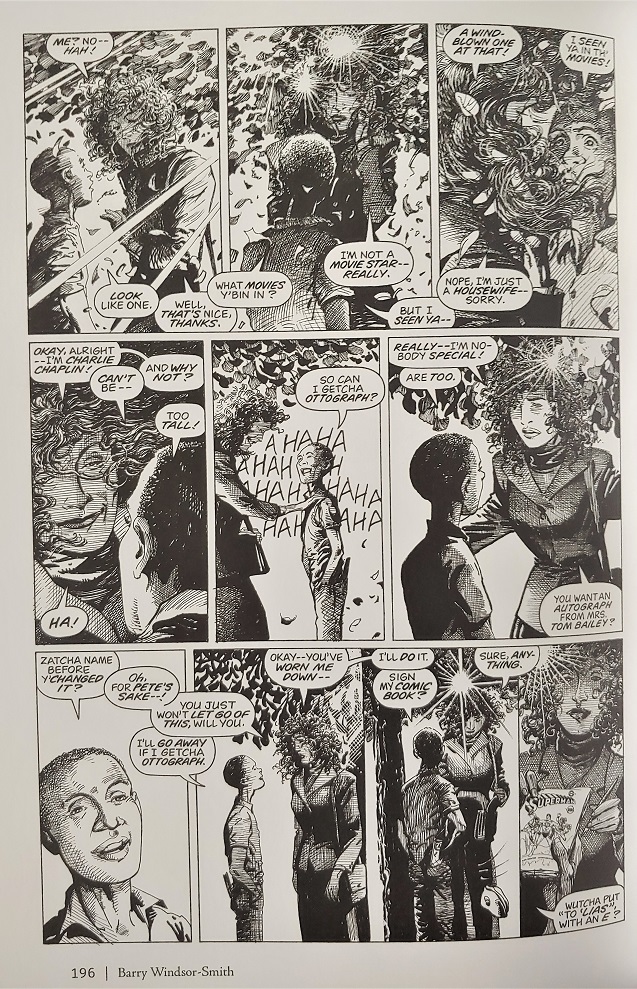

When I started reading the first pages, my immediate thought was that the whole story would revolve exclusively around Bobby Bailey. I was wrong. Very early on, Sergeant Elias McFarland becomes a very important character, and we get to see how he lives, how it is to be a black man at a time in which even voting wasn’t allowed for black people. But what’s more fascinating is to see the way McFarland becomes depressed and falls to pieces after sending Bobby, an innocent kid, into the hands of a sinister military scientist. The way McFarland starts his low descent into madness is one of the most fascinating moments, everything is meticulously described, and thanks to the fantastic art, we immediately feel as if we were living with McFarland, and we experience the pain and the suffering of the family, we relate to McFarland’s wife, his son, his daughter, we understand pain, we make it ours, and then we have no choice but to let go of it.

As part of a metafictional game, we see McFarland spending entire days in the basement, with his comic book collection, real covers of Superman, Batman, Flash or Captain America are firmly inserted in the panels, which of course begs the question of what is the connection between these childish almost primitive comics compared to this phenomenal and very adult graphic novel. But all the connections are there, and like I said before, in the same way that Windsor-Smith is the embodiment of the history of Western art and comic book trends, this story also summarizes the history of comic book, establishing links, highlighting differences and embracing similarities in one sweeping scoop.

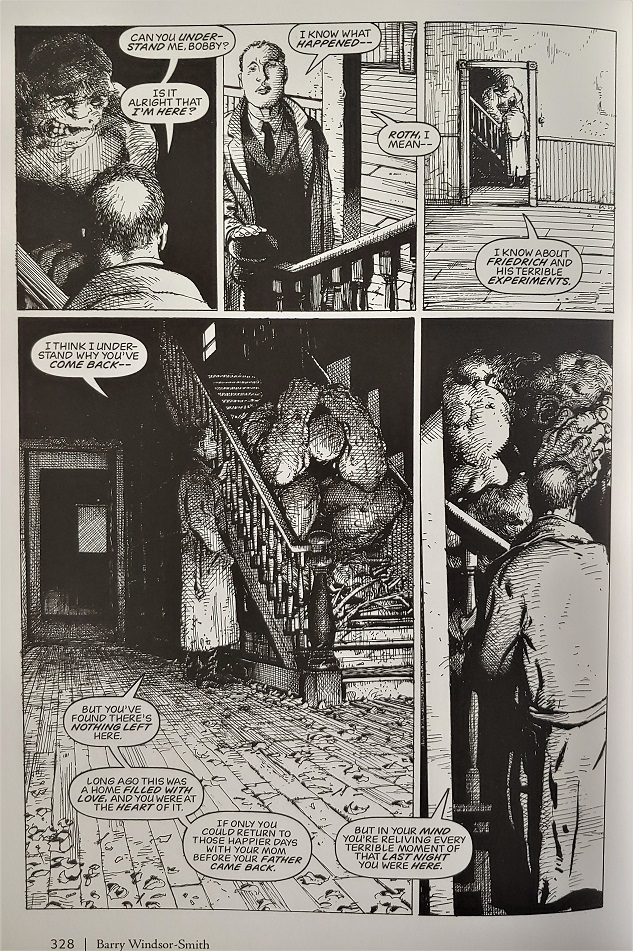

After one becomes familiarized with McFarland there’s another shift in point of view and perspective. We see the officials behind the Prometheus project, we see the ‘behind the scenes’ of the inhuman experiments conducted in secret, and as part of our peripheral view, we also get a glimpse of what’s going on with Bobby Bailey. With the help of his only ally, Bailey is able to escape. At this point, I immediately assumed we would be reading about a modern day Frankenstein but not really. Bailey returns home, and as he approaches his old house, the memories of his childhood start pouring down.

Suddenly we’re in the 40s, Bobby is a child, and his mother and father are living in a nightmare. Mr. Bailey returned from WWII a changed man, before the war he was a cheerful, enthusiastic young man, always willing to do anything to make his girl laugh out loud. Now he’s an angry man, he has aged decades in just a few years, he’s bitter, resentful and incredibly aggressive. Mrs. Bailey had prayed for so long to see her husband coming back from war in one piece, and now that he’s there, she almost wishes he had passed away on the battlefield. The man has turned into a monster, besieged by the war crimes committed by the Nazis, he spends the entire day getting drunk and using alcohol as an excuse to be physically aggressive, what’s worse, poor, defenseless Bobby Bailey is very often the victim of his enraged father. Although the circumstances might sounds melodramatic, Windsor-Smith writes with such intensity, pure emotion and courage, that this feels more like a documentary, like reading the intimate diary of a wife dealing with a man that once made her happy and now only makes her miserable. The real suffering, however, is yet to come. After all, in the words of Jan Paul Sartre, “l'enfer, c'est les autres” (‘hell is the others’).

Once again, when we think we’re able to predict what’s going to happen next, the author throws another curve ball at us. Now we’re a couple of years in the past, before the return of the husband. Mrs. Bailey is spending a lot of time with officer Powell. Here we discover the unique personality, the gentle heart and the resilience of a woman who dreams about reuniting with her husband. There is so much going on here, there is the subtle romantic interest that shows up in the form of Mr. Powell, but there is also the dynamics of life as a single woman, the bargaining with society in terms of what is allowed or not for a young female. Of course, there are extraordinary moments, like the scene in which Mrs. Bailey has a short conversation with a very young Elias McFarland, decades before he’ll become a sergeant. Finally, a portion of the story also revolves around the Nazi officer in charge of the Prometheus project, and perhaps this could be the only controversial part as I’m sure many LGBT allies will complain about what is apparently a negative portrayal of homosexuality, however I’d like to think that there is a deeper meaning in the scenes in which two German men share an intimate bond that goes beyond their allegiance to the Third Reich.

Barry Windsor-Smith always had the ability to come up with the most outlandish situations and make them real. But this time he’s also weaving a complex tapestry in which every character and every situation fits in perfectly, we can only get to see the big picture at the end, after engaging in this fascinating polyphonic dialogue with multiple characters, across multiple timelines: “Windsor-Smith has been working on this passion project for more than 35 years, and Monsters is part intergenerational family drama, part espionage thriller, and part metaphysical journey. Trauma, fate, conscience, and redemption are just a few of the themes that intersect in the most ambitious (and intense) graphic novel of Windsor-Smith's career”. Yes, it’s the most ambitious and the most intense, but also the most beautiful, the most unforgettable. I said it was a masterpiece and I’ll say it again. Nothing comes close to it. What a remarkable graphic novel.

________________________________________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________________________________________

A Barry Windsor-Smith le ha llevado una cantidad considerable de años concebir y crear su magnum opus, Monsters, una obra maestra diferente a todo lo que he visto antes y que ha llegado en el momento adecuado. Cuando comencé este blog, hace más de una década, estaba impaciente por hablar de una de las mejores etapas de cómics de la historia: Conan the Barbarian de Roy Thomas y Barry Windsor-Smith. Reseñé cada número de Conan ilustrado por el talentoso artista británico y disfruté la experiencia de volver a leerlo todo. Ver la evolución de Windsor-Smith en las páginas de Conan fue como ver una combinación de tendencias de cómics y una historia del arte occidental, siglos enteros condensados en uno o dos meses. Adoptando múltiples estilos y refinando su técnica, Windsor-Smith se convirtió rápidamente en el mejor artista de los 70s.

Monsters es el resultado de todo lo que Barry Windsor-Smith ha aprendido en su larga y fructífera carrera. En el pasado, solía imaginar al artista británico inspirándose en Rembrandt, Goya, El Greco o incluso en Auguste Rodin. Para Neil Gaiman, sin embargo, la influencia más importante es la del Renacimiento y el Manierismo, y ciertamente puedo percibir fácilmente la influencia de la obra de genios como Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo Buonarroti, Rafael Sanzio, Sandro Botticelli, Donatello y Benvenuto Cellini. A veces, una página de Windsor-Smith puede evocar los dibujos en tiza roja de Leonardo o los grabados de Rafael.

Además, en su último período en Conan, la obra de arte de Windsor-Smith me recordó los dibujos en tinta de Albrecht Dürer, y su entorno naturalista también era un homenaje a las pinturas de Hieronymus Bosch. A lo largo de todas estas páginas, sin embargo, permanece una constante: la belleza, o más bien, como solía llamarla Schilling, un pathos sublime que lleva los conceptos estéticos a un nivel completamente nuevo. Ningún otro dibujante en la historia del cómic, con la excepción quizás de Hal Foster y Frank Frazetta, y algunos discípulos de Windsor-Smith, ha conjugado tan magistralmente la historia artística de nuestra civilización, y nadie más ha sido capaz de equilibrar todo esto con dinamismo, energía vibrante y el ritmo único del medio del cómic. Decir que Barry Windsor-Smith es simplemente un artista nunca sería suficiente porque él es El Artista; él es todos los artistas que han existido antes, y todas las infinitas posibilidades del arte bajo el dominio de una mente lúcida y dos manos extremadamente capaces.

|

| 1942: Mrs. Bailey & Elias McFarland |

Una vez más, Barry Windsor-Smith sintetiza la historia del arte occidental, por lo que tras el Renacimiento y el Manierismo también tenemos elementos influidos por el barroco y el romanticismo. Y páginas intensas que se asemejan a las obras de Caravaggio. Con el paso de las décadas, Barry Windsor-Smith ha abrazado por completo el movimiento expresionista, y en lugar de un Albrecht Dürer trabajando para Marvel, se parece más a un Francis Bacon que regresa a la Casa de las Ideas (para Michael Zulli, por ejemplo, esto es el período más interesante de Windsor-Smith). La evolución artística, al fin y al cabo, es la clave para entender la carrera de este incomparable artista británico.

En Monsters, Windsor-Smith encuentra el equilibrio por el que tantos luchan y muy pocos logran. Conserva lo mejor de sus influencias renacentistas y manieristas, conservando también los aspectos que mejor sirven a la narración gráfica, aquellos aspectos adquiridos durante sus días más expresionistas. El resultado es una obra de arte absolutamente hermosa. 360 páginas que continuarán dejándome asombrado y completamente sin aliento. Pensé en analizar cada página de esta novela gráfica original, pero sinceramente no creo que sea práctico tener una reseña de casi 400 páginas. Baste decir que quedé absolutamente fascinado por el arte aquí. Este es también el mejor arte en blanco y negro que he visto en el siglo XXI, no creo que nada más pueda compararse con él. Cada vez que veo algo en blanco y negro, siempre siento que falta el color, esta es la primera vez que siento que el color sería una interferencia. La forma en que Windsor-Smith usa el contraste, la luz y la sombra, la profundidad y la perspectiva, haría que el color fuera redundante aquí.

|

| 1945: Mr. Bailey |

Hasta ahora sólo he hablado de Barry Windsor-Smith el artista, pero ahora es el momento de hablar de Barry Windsor-Smith el escritor. Pocas veces en mi vida he leído un guión más inteligente, mejor elaborado, complejo, multifacético, atrapante y cautivador como el de Monsters. Ya había expresado mi admiración por Windsor-Smith como autor completo, cuando hizo Weapon X, pero Monsters es mucho mejor: “en 1964, Bobby Bailey es reclutado para un programa militar estadounidense de genética experimental que fue descubierto en la Alemania nazi hace 20 años. Su único aliado, el sargento McFarland, interviene para tratar de protegerlo, lo que desencadena una cadena de eventos que escapan al control de todos. A medida que los monstruos titulares se multiplican, volviéndose reales y metafóricos, literales e irónicos, la historia alcanza su ajuste de cuentas emocional y moral”. Para muchos, esto puede parecer un tema típico de cómic, la experimentación genética y los nazis, pero en realidad es mucho más. Porque esto es apenas la punta del iceberg.

Cuando comencé a leer las primeras páginas, mi pensamiento inmediato fue que toda la historia giraría exclusivamente en torno a Bobby Bailey. Estaba equivocado. Muy pronto, el sargento Elias McFarland se convierte en un personaje muy importante, y podemos ver cómo vive, qué significa ser un hombre negro en un momento en el que ni siquiera se les permitía votar a los afroamericanos. Pero lo que es más fascinante es ver la forma en que McFarland se deprime y se desmorona después de enviar a Bobby, un chiquillo inocente, a manos de un siniestro científico militar. La forma en que McFarland inicia su descenso a la locura es uno de los momentos más fascinantes, todo está minuciosamente descrito y gracias al arte fantástico inmediatamente nos sentimos como si estuviéramos viviendo con McFarland, y experimentamos el dolor y el sufrimiento de la familia, nos relacionamos con la esposa de McFarland, su hijo, su hija, entendemos el dolor, lo hacemos nuestro, y luego no tenemos más remedio que dejarlo ir.

Como parte de un juego de metaficción, vemos a McFarland pasar días enteros en el sótano, con su colección de cómics, portadas reales de Superman, Batman, Flash o Capitán América están firmemente insertadas en las viñetas, lo que por supuesto plantea la pregunta de cuál es la conexión entre estos cómics infantiles casi primitivos en comparación con esta novela gráfica fenomenal y muy adulta. Pero todas las conexiones están ahí, y como dije antes, de la misma manera que Windsor-Smith es la encarnación de la historia del arte occidental y las tendencias del cómic, Monsters también resume la historia del cómic, estableciendo vínculos, destacando las diferencias y abarcando similitudes.

Después de que uno se familiariza con McFarland, hay otro cambio en el punto de vista y la voz narrativa. Vemos a los funcionarios detrás del proyecto Prometheus, vemos el "detrás de escenas" de los experimentos inhumanos realizados en secreto y, como parte de nuestra visión periférica, también podemos vislumbrar lo que está pasando con Bobby Bailey. Con la ayuda de su único aliado, Bailey logra escapar. En este punto, inmediatamente asumí que estaríamos leyendo sobre un Frankenstein moderno, pero no realmente. Bailey regresa a casa y, a medida que se acerca a su antiguo hogar, los recuerdos de su infancia salen a flote.

|

| 1965: Bobby Bailey |

De repente estamos en los 40s, Bobby es un niño y su madre y su padre viven en una pesadilla. El Sr. Bailey regresó de la Segunda Guerra Mundial como un hombre diferente, antes de la guerra él era un joven alegre y entusiasta, siempre dispuesto a hacer cualquier cosa para hacer reír a carcajadas a su chica. Ahora es un hombre enojado, ha envejecido décadas en tan sólo unos años, está amargado, resentido y es increíblemente agresivo. La Sra. Bailey rezaba para ver a su esposo regresar de la guerra en una sola pieza, y ahora que él está allí, casi desea que haya fallecido en el campo de batalla. El hombre se ha convertido en un monstruo, asediado por los crímenes de guerra cometidos por los nazis, se pasa el día entero emborrachándose y usando el alcohol como excusa para ser físicamente agresivo, lo que es peor, el pobre e indefenso Bobby Bailey es muchas veces víctima de su padre enfurecido. Aunque las circunstancias puedan sonar melodramáticas, Windsor-Smith escribe con tal intensidad, pura emoción y valentía, que esto se siente más como un documental, como leer el diario íntimo de una esposa que trata con un hombre que una vez la hizo feliz y ahora sólo la hace infeliz. El verdadero sufrimiento, sin embargo, aún está por llegar. Después de todo, en palabras de Jan Paul Sartre, “l'enfer, c'est les autres” (“el infierno son los otros”).

Una vez más, cuando creemos que podemos predecir lo que sucederá a continuación, el autor nos lanza otra bola curva. Ahora estamos un par de años en el pasado, antes del regreso del esposo. La Sra. Bailey pasa mucho tiempo con el oficial Powell. Aquí descubrimos la personalidad única, el corazón tierno y la resistencia de una mujer que sueña con reencontrarse con su marido. Vemos el sutil interés romántico que aparece en la forma del Sr. Powell, pero también está la dinámica de la vida como una mujer soltera, la negociación con la sociedad en términos de lo que está permitido o no para una mujer joven. Por supuesto, hay momentos extraordinarios, como la escena en la que la Sra. Bailey tiene una breve conversación con un jovencísimo Elias McFarland, décadas antes de convertirse en sargento. Finalmente, una parte de la historia también gira en torno al oficial nazi a cargo del proyecto Prometheus, y tal vez esta podría ser la única parte controversial, ya que estoy seguro de que algunos lectores LGBT se quejarán de lo que aparentemente es una representación negativa de la homosexualidad. Me gustaría pensar que hay un significado más profundo en las escenas en las que dos hombres alemanes comparten un vínculo íntimo que va más allá de su lealtad al Tercer Reich.

Barry Windsor-Smith siempre tuvo la capacidad de idear las situaciones más extravagantes y hacerlas reales. Pero esta vez también está tejiendo un tapiz complejo en el que cada personaje y cada situación encajan perfectamente, sólo podemos ver el panorama general al final, después de participar en este fascinante diálogo polifónico con múltiples personajes, a través de múltiples líneas de tiempo: "Windsor -Smith ha estado trabajando en este apasionante proyecto durante más de 35 años, y Monsters es en parte un drama familiar intergeneracional, en parte un thriller de espionaje y en parte un viaje metafísico. Trauma, destino, conciencia y redención son sólo algunos de los temas que se entrecruzan en la novela gráfica más ambiciosa (e intensa) de la carrera de Windsor-Smith”. Sí, es la más ambiciosa y la más intensa, pero también la más bella, la más inolvidable. Dije que era una obra maestra y lo diré de nuevo. Nada se le acerca. Una notable novela gráfica.