So what happens with those forgotten heroes that had the misfortune of being popular years before Marvel productions became a hit? What happens is quite simple: we talk about them, and we remember why they were important for us years ago. In the early 90s, legendary writer Dennis O’Neil and future Marvel Editor In Chief Joe Quesada were the creative team behind Azrael, a hero that became so popular that had his own title.

As much as I would like to be objective, I can’t remember why Azrael was so important for me, maybe it was because I absolutely enjoyed Quesada’s art, or simply because my father got me the original miniseries as a gift. In the end, however, it doesn’t matter how much nostalgia or aesthetics are involved, what matters the most is that, many years later, I’m still interested in this hero, and in many others, that for one reason or another never made it to the big screen.

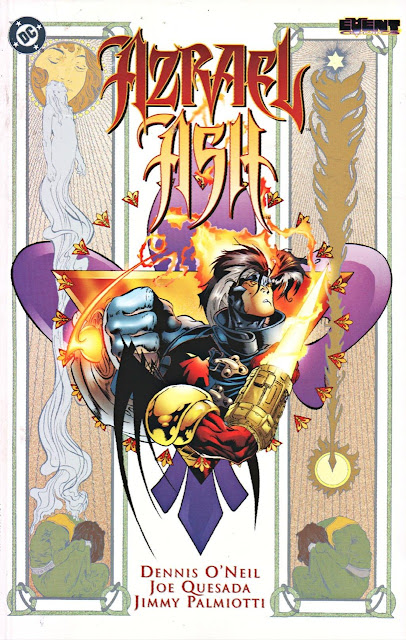

In 1997 DC and the now disappeared publisher Event Comics worked together to produce Azrael / Ash, a special one-shot that reunited Azrael’s original creative team (O’Neil and Quesada), and also Quesada’s own creation, Ash. Unlike other intercompany crossovers, these two young heroes were actually a perfect match: from their physical appearance to their special abilities, and their unique connection to fire, everything was conducive to a memorable first meeting.

In only 48 pages, O’Neil builds up suspense, introduces a mysterious threat and highlights the similitudes between Ash, a superhero with the ability to control fire, and Azrael, a superhero who uses flaming blades. The two main adversaries also possess fire-related powers. However, O’Neil’s greatest narrative strength relies on the way he fleshes out the alter egos of Ash and Azrael, Ashley Quinn and Jean Paul Valley are two young men, barely out of their teens, still trying to figure out their identities as well as their roles as superheroes. For Ashley Quinn, using his powers is an intoxicating practice that “sends waves of pleasure rippling through him: an overwhelmingly sensuous experience”; for Jean Paul Valley, on the contrary, the act of becoming Azrael is unpleasant: “he hates it, for even as it confers superhuman abilities on him, it robs him of who he is”.

|

| Batman & Jean Paul Valley |

________________________________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________________________________

Hoy en día los personajes de los cómics aparecen constantemente en todas partes: dibujos animados, series de televisión, películas, etc. Ciertos superhéroes han alcanzado una popularidad que nadie podría haber soñado hace una década. Pero por cada serie o película que retrata a docenas de personajes, todavía quedan cientos en la oscuridad.

|

| Ashley "Ash" Quinn & Jean Paul Valley |

|

| Azrael versus Firefly |

Por mucho que me gustaría ser objetivo, no recuerdo por qué Azrael era tan importante para mí, tal vez fue porque disfrutaba mucho con el arte de Quesada, o simplemente porque mi padre me regaló la miniserie original. Al final, sin embargo, no importa cuánta nostalgia o estética haya de por medio, lo que más importa es que, muchos años después, todavía estoy interesado en este héroe, y en muchos otros, que por una razón u otra nunca llegaron a la gran pantalla.

En 1997 DC y la desaparecida editorial Event Comics trabajaron juntos para producir Azrael / Ash, un one-shot especial que reunió al equipo creativo original de Azrael (O'Neil y Quesada), y también a la propia creación de Quesada, Ash. A diferencia de otros crossovers intercompañía, estos dos jóvenes héroes eran en realidad una pareja perfecta: desde su apariencia física hasta sus habilidades especiales, y su conexión única con el fuego, todo fue propicio para una primera reunión memorable.

En sólo 48 páginas, O'Neil crea suspenso, presenta una amenaza misteriosa y resalta las similitudes entre Ash, un superhéroe con la capacidad de controlar el fuego, y Azrael, un superhéroe que usa dagas flamígeras. Los dos principales adversarios también poseen poderes relacionados con el fuego. Sin embargo, la fortaleza narrativa de O'Neil se basa en la forma en que él desarrolla los alter egos de Ash y Azrael, Ashley Quinn y Jean Paul Valley son dos jóvenes, que apenas han dejado atrás la adolescencia, que aún tratan de descubrir sus identidades, así como sus roles como superhéroes. Para Ashley Quinn, usar sus poderes es una práctica intoxicante que "envía oleadas de placer a través de él: una experiencia abrumadoramente sensual"; para Jean Paul Valley, por el contrario, el acto de convertirse en Azrael es desagradable: "él lo odia, porque incluso si aquello le confiere habilidades sobrehumanas, pierde su identidad en el proceso".

|

| Ash |