|

| Adam Hughes |

But, what is the origin of beauty? In every civilization, there have been myths and legends of women of undisputable beauty. Willingham takes the female characters from the most well-known fairy tales and tries to delve into their pasts. As Briar Rose hears the story of her origin, many questions about the nature of beauty arise.

Can Rose or Snow Queen be truly beautiful if they are immortal? The nature of Beauty, for example, as Plato understands it, is the essence of the unobtainable. And what is one's relationship to beauty? Beauty is nothing but a veil that we use to cover up the horror of mortality; according to Nietzsche beauty can be found in true art, according to Kant beauty exists because death exists, and beauty is that which reminds us of death while at the same time reaffirms our vital urges. Ultimately, beauty veils the real, covers and masks the certainty of death. However, as these two women bask in their immortality, do they redefine the concept of beauty or, at least, undermine it?

|

____________________________________________________________________________________________

Para aquellos que han leído Fables, ya saben que los personajes clásicos de los cuentos para niños pueden transformarse en alegorías o arquetipos contemporáneos. Bill Willingham parece tener un montón de ideas sobre hadas y princesas, y tal vez las páginas de Fables no eran suficientes para contenerlas. Por tanto, tenemos esta nueva serie, Fairest, en la que nos enfocamos en preciosas princesas y bellas doncellas.

Pero, ¿cuál es el origen de la belleza? En cada civilización, ha habido mitos y leyendas sobre mujeres de belleza indiscutible. Willingham intentan indagar en el pasado de estos conocidos personajes. Cuando Briar Rose escucha su historia de origen, empiezan las preguntas sobre la naturaleza de su belleza.

¿Pueden Rose o la Reina de las Nieves ser realmente hermosas si son inmortales? La naturaleza de lo bello, por ejemplo, tal como lo entiende Platón, es la esencia de lo inobtenible. ¿Y cuál es nuestra relación con lo bello? Lo bello no es nada más que un velo que usamos para cubrir el horror de la mortalidad; de acuerdo con Nietzsche lo bello puede encontrarse en el arte, de acuerdo con Kant lo bello existe porque la muerte existe, y lo bello es aquello que nos recuerda la muerte al mismo tiempo que reafirma nuestros impulsos vitales. En última instancia, lo bello vela lo real, cubre y enmascara la certeza de la muerte. Sin embargo, mientras estas dos mujeres se regodean en su inmortalidad, ¿redefinen el concepto de belleza o lo debilitan?

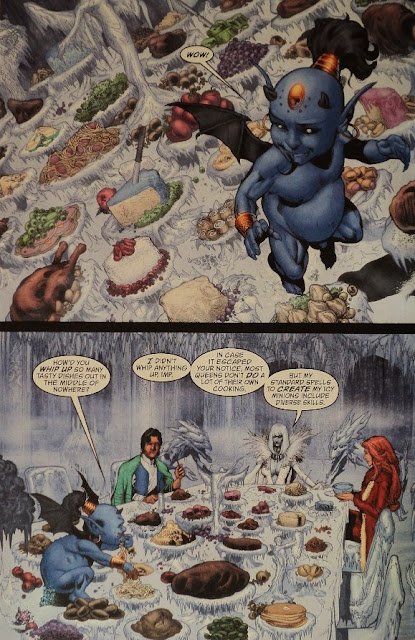

Dejando a un lado las cuestiones filosóficas, una cosa es clara: Lo bello está también presente en el maravilloso arte de Phil Jimenez. Él encuentra el balance entre el misterio y lo extravagante en sus diseños para la primera página; luego ilustra a la Reina de las Nieves de manera refinada y seductora. La escena del banquete es muy imaginativa, y la página con el laberinto de hielo nos deja sin aliento. La composición y el amor por los detalles caracterizan el trabajo de este talentoso artista. Andy Lanning y Mark Farmer son entintadores de primer nivel, y Andrew Dalhouse aprovecha los tonos fríos para transmitir la frialdad de la Reina de las Nieves, mientras incluye piscas de colores vívidos para impedir la monotonía. Adam Hughes dibuja una asombrosa portada. Un fantástico equipo creativo. Un cómic realmente bello.