Whenever I say John Byrne was the greatest creator of the 80s, I immediately have to clarify that Byrne was a great writer and a great artist, but as amazing as he was, on the artistic level I don’t think he could’ve surpassed George Pérez. And unlike Byrne, Pérez continued to be magnificent after the 80s, and well into the 90s and the 00s and if not for his current health conditions he would still be absolutely marvelous today. In terms of art I don’t think anyone could rival Pérez at the time, but so often we forget that in addition to his incredible artistic talent, Pérez was also a fantastic writer.

In the 80s, after Miller’s Batman: Year One and after Byrne’s The Man of Steel, the two quintessential superhero origin stories, Pérez accepted the challenge to revitalize Wonder Woman, and he was very successful revamping such a classic character. Talking with comic book expert Guido Cuadros, we both agree on the fact that the 80s was a glorious era for DC but also the only time in which we could get 3 absolutely fascinating origin stories that are still as impressive today as they were over 30 years ago.

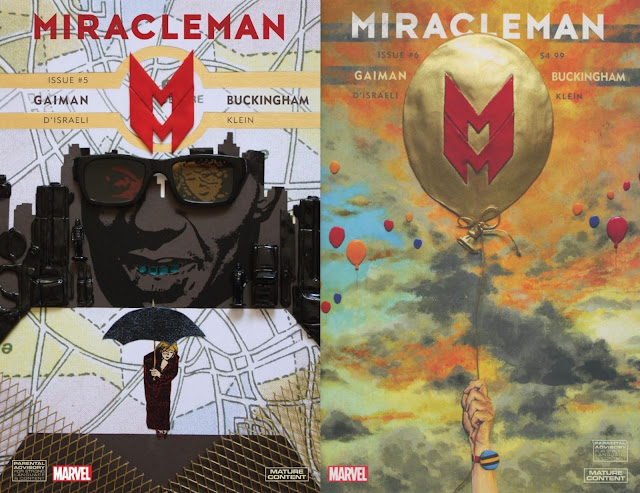

|

| Olympus |

“The Princess and the Power” (originally published in Wonder Woman # 1, February 1987) tells the story of Diana, and before that the story of Themyscira and queen Hippolyte (Diana’ mother), and before that the story of Ancient Greece and Olympus, and the story of gods and demigods that we’re all familiar with. This 32 page special would surely be a 6 or 12-issue miniseries nowadays, but back in the 80s they really knew how to condense a story, this one packs quite a punch instead of being the typically diluted and decompressed comic of the 21st century.

|

| Amazons |

The first issues of Wonder Woman were coplotted by Greg Potter and George Pérez, and fortunately they had the brilliant idea of explaining first the origin of the amazons and the constant conflict between the gods of Olympus. Athena, Artemis, Demeter, Hestia and Aphrodite are responsible for the creation of the amazons, whose mission in life is to inspire people. Of course, this enrages Ares, god of war, who will be a formidable opponent in future issues.

|

| Ares |

The most surprising moment in the comic is when Herakles (also known as Hercules in the Roman mythology) deceives and rapes Hyppolite. As I’ve mentioned before in the blog, in 2011 there was a movement of comic book writers rejecting rape in fiction and refusing to write stories in which someone was raped. So this comic book would’ve been impossible to publish today. Pérez depicts the incarceration and the abuse in a tasteful manner. The battle between the amazons and Herakles’ men is one of the best pages ever! Pérez creates such a powerful composition which revolves around a central sword and 8 panels around it, showing the attack more in detail.

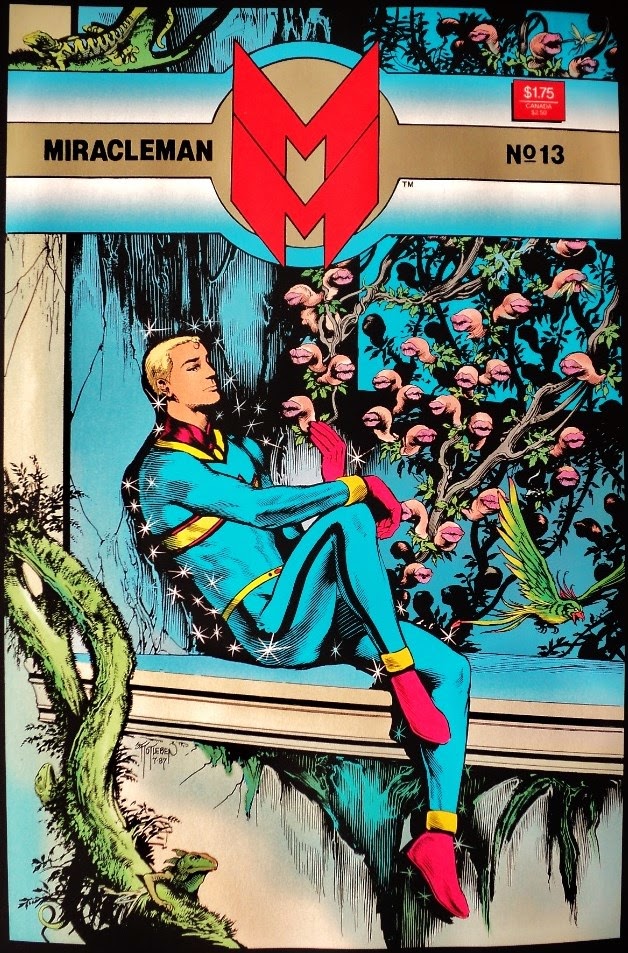

Of course, the wraparound cover and the last page are absolutely beautiful. The cover is especially meaningful since it tells pretty much the entire story with just a few images! George Pérez’s pencils are inked by Bruce Patterson, and the colors are by Tatjanna Wood. For this truly wonderful artistic team, computers were not necessary to create beauty. And although the original editions of this comic were printed in cheap, bulky paper, now DC is reediting all of this in the Wonder Woman omnibus editions (I already got the first one).

If there is a reason why current Wonder Woman comics have failed both with readers and critics is because they’ve tried to avoid that fundamental violence at its core and also they have attempted to remove all elements of sexuality. According to Greg Grandin “violence is an essential component of state consolidation, in order to serve the purpose of nationalism, it needs to be ritualized, as Benedict Anderson puts it, ‘remembered / forgotten as our own’”. In short, the creation of Themyscira as an independent nation can only be possible if there is a fundamental violence, which is courageously portrayed by Pérez in this comic. The mistake of all current writers has been trying to remove all these elements and pretend that Themyscira started as a nation simply because the gods willed it.

________________________________________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Siempre que digo que John Byrne fue el mejor creador de los 80s, inmediatamente debo aclarar que Byrne fue un gran escritor y un gran artista, pero por asombroso que fuera, a nivel artístico no creo que pudiera haber superado a George Pérez. Y a diferencia de Byrne, Pérez siguió siendo magnífico después de los 80s, y hasta bien entrados los 90s y los 2000s y si no fuera por sus condiciones de salud actuales, todavía sería absolutamente maravilloso hoy. En términos de arte, nadie hubiese podido rivalizar con Pérez en ese momento, pero muchas veces olvidamos que, además de su increíble talento artístico, Pérez también fue un escritor fantástico.

|

| Hyppolite & Herakles |

En los 80s, después de Batman: Year One de Miller y después de The Man of Steel de Byrne, las dos historias de origen de superhéroes por excelencia, Pérez aceptó el desafío de revitalizar a Wonder Woman, y tuvo mucho éxito renovando un personaje tan clásico. Hablando con el experto en cómics Guido Cuadros, ambos estamos de acuerdo en el hecho de que los 80s fue una era gloriosa para DC, pero también la única vez en la que hubo 3 historias de origen absolutamente fascinantes que siguen siendo tan impresionantes hoy como lo fueron hace más de 30 años.

"La princesa y el poder" (publicado originalmente en Wonder Woman # 1, febrero de 1987) cuenta la historia de Diana, y antes de eso, la historia de Themyscira y la reina Hipólita (la madre de Diana), y antes de eso, la historia de la antigua Grecia y el Olimpo, y la historia de los dioses y semidioses con la que todos estamos familiarizados. Este especial de 32 páginas seguramente sería una miniserie de 6 o 12 números en la actualidad, pero en los 80s realmente sabían cómo condensar una historia, esta es muy impactante en lugar de ser el cómic típicamente diluido y descomprimido del siglo XXI.

|

| the great battle / la gran batalla |

Los primeros números de Wonder Woman fueron co-argumentados por Greg Potter y George Pérez, y afortunadamente ellos tuvieron la brillante idea de explicar primero el origen de las amazonas y el constante conflicto entre los dioses del Olimpo. Atenea, Artemisa, Deméter, Hestia y Afrodita son las responsables de la creación de las amazonas, cuya misión en la vida es inspirar a las personas. Por supuesto, esto enfurece a Ares, dios de la guerra, quien será un oponente formidable en futuros capítulos.

El momento más sorprendente del cómic es cuando Heracles (también conocido como Hércules en la mitología romana) engaña y viola a Hipólita. Como mencioné antes, en el blog, en el 2011 hubo un movimiento de escritores de cómics que rechazaron la violación en la ficción y se negaron a escribir historias en las que alguien fuese violado. Por tanto, este cómic hubiera sido imposible de publicar el día de hoy. Pérez describe el encarcelamiento y el abuso de una manera elegante. ¡La batalla entre las amazonas y los hombres de Heracles es una de las mejores páginas de la historia! Pérez crea una composición tan poderosa que gira en torno a una espada central y 8 viñetas a su alrededor, que muestran el ataque con más detalle.

|

| Wonder Woman |

Por supuesto, la portada doble y la última página son absolutamente hermosas. ¡La portada es especialmente significativa ya que cuenta casi toda la historia con sólo unas pocas imágenes! Los lápices de George Pérez están entintados por Bruce Patterson y los colores son de Tatjanna Wood. Para este equipo artístico verdaderamente de maravilla, las computadoras no eran necesarias para crear belleza. Y aunque las ediciones originales de este cómic se imprimieron en papel de baja calidad y con colores pobres, ahora DC está reeditando todo esto en las ediciones Omnibus de Wonder Woman (ya me compré la primera).

Si hay una razón por la que los cómics actuales de Wonder Woman han fallado tanto con los lectores y con los críticos es porque han tratado de evitar esa violencia fundamental en su núcleo y también han intentado eliminar todos los elementos de sexualidad. Según Greg Grandin, “la violencia es un componente esencial de la consolidación del Estado, para que sirva al propósito del nacionalismo, debe ser ritualizada, como dice Benedict Anderson, 'recordada / olvidada como nuestra'”. En definitiva, la creación de Themyscira como nación independiente solo puede ser posible si hay una violencia fundamental, que es retratada con valentía por Pérez en este cómic. El error de todos los escritores actuales ha sido intentar eliminar todos estos elementos y pretender que Themyscira comenzó como nación simplemente porque los dioses así lo desearon.