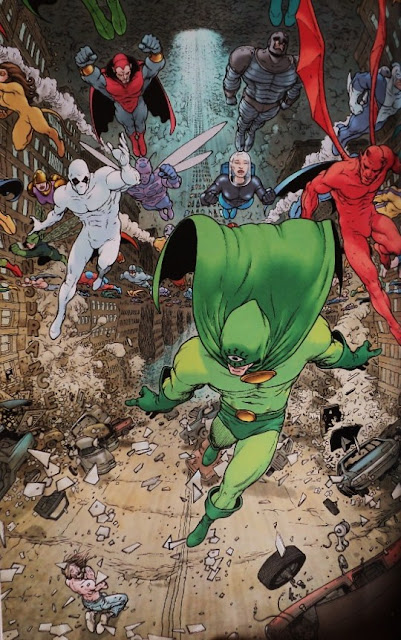

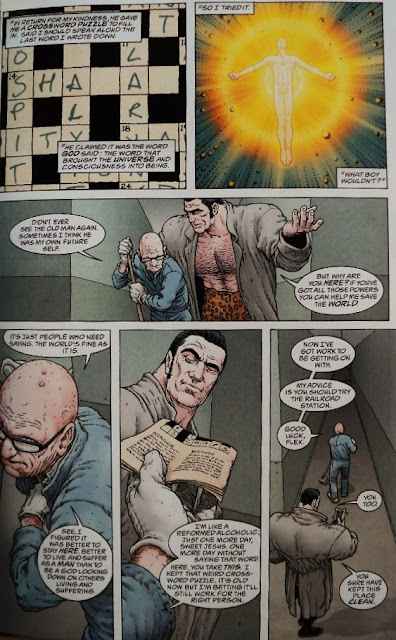

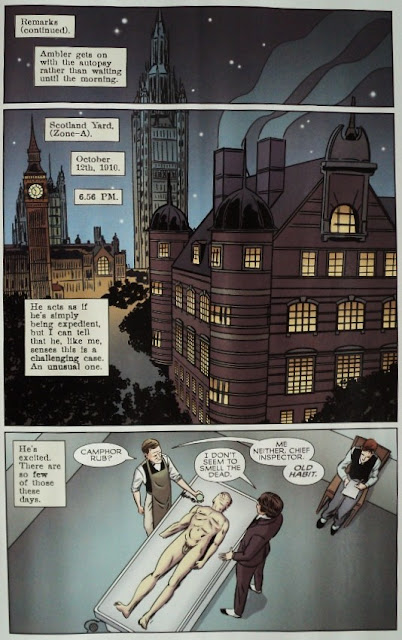

Elle Peterssen, a normal girl, is attacked at the subway station. She has no enemies and yet a lot of people seemed to be after her. Now that she is in a comma, her friends and relatives try to get some answers. What is the mystery behind her attackers? And why on Earth does she have more brain activity than any normal human being (comatose condition not withstanding)?

I must admit I had never read anything from Jim McCann before, although I had interacted with him a few times on the Bendis board. When I saw he was launching his new creator-owned project I became interested. Perhaps I felt like I owed him a chance after talking online with him. But there is something else that seduced me about this project: Rodin Esquejo. If I would have to choose my favorite new cover artist from the past couple of years it would be Esquejo. I remember one of the main reasons that made me buy the first issue of Morning Glories was his amazing cover. And now I had the chance to see him doing interior art, of course I wasn’t going to miss that!

And I’m glad I preordered the first issue of Mind the Gap. Jim has written a pulse pounding thriller, with emotion, action, drama and some humorous moments; not only that, he manages to flesh out the main characters of the series while including a bunch of eater eggs that detail-loving fans such as myself will be grateful for.

There is something else that I really enjoyed about this opening chapter. Elle is an in-between place, she’s neither death nor fully alive. She is in a comma but she is also conscious on a strange and ethereal limbo. I consider this an interesting approach to Jacques Lacan's concept of symbolic death. I’ll try to explain it in simple words: There is an impasse between symbolic death and actual (real) death. Because death is not only the absence of life, it’s so much more than that, especially to us. The need for a symbolic death becomes patently necessary for people. Lacan defined the symbolic death as a narrative of closure, as the final sentence one must utter in order to let go of the dead ones. If every culture in the planet respects some sort of funerary rites it is precisely because of that. The real death comes naturally when a heart stops beating, but the symbolic death is something cultural, something that depends on any given individual and the ability to cope with loss. Coming to terms with death means to be able to write that epitaph in our head, to be able to understand someone else's life and then to let go of it.

So I consider that Elle is an especially courageous girl, as she hears others talking about her as if she were dead and still refuses to believe that this is the end. Can her consciousness return to her body? Nobody knows, but there’s one thing that worries her, if the people that tried to kill her failed, then it won’t be long before they come after her. Once again, Image is giving us a very promising new series with absolutely fantastic art by Rodin Esquejo and vibrant colors by Sonia Oback. And we should also admire the gorgeous logo design by Michael Lapinski (not only one of my friends from the Bendis board but also an author that has contributed to The Gathering just I have more than a few times). Mind the Gap is definitely worth checking out. I highly recommend it.

_________________________________________

_________________________________________

Elle Peterssen, una chica normal, es atacada en la estación del metro. No tiene enemigos y sin embargo mucha gente la persigue. Ahora que está en coma, sus amigos y familiares intentan encontrar algunas respuestas. ¿Cuál es el misterio detrás de sus atacantes? ¿Y por qué, a pesar de estar en coma, su cerebro registra una actividad por encima de cualquier escala?

Debo admitir que nunca había leído algo de Jim McCann antes, aunque había interactuado con él varias veces en la página de Bendis. Cuando vi que anunciaba su nuevo proyecto personal, me interesé. Tal vez sentí que le debía una oportunidad después de hablar con él vía internet. Pero hay algo más que me sedujo sobre este proyecto: Rodin Esquejo. Si tuviera que elegir a mi nuevo portadista favorito de los últimos dos años sería Esquejo. Recuerdo que una de las principales razones que me llevaron a comprar el primer ejemplar de Morning Glories fue su asombrosa portada. Y ahora que tenía la oportunidad de verlo dibujando absolutamente todo, sabía que no podía pasar esto por alto.

Y me alegra haber comprado el primer número de "Mind the Gap" por adelantado. Jim ha escrito un thriller intenso, con emoción, acción, drama y algunos momentos humorísticos; no sólo eso, se las ha arreglado para darle forma a los personajes principales y también ha incluido algunas pistas ocultas que los fans atentos al detalle sabrán apreciar.

Hay algo más que disfruté de este capítulo inicial. Elle está en el 'entre dos mundos', no está muerta ni viva del todo. Está en coma pero también está consciente en un extraño y etéreo limbo. Considero que este es un interesante enfoque al concepto de muerte simbólica de Jacques Lacan. De manera resumida, hay un impasse entre la muerte simbólica y la muerte de hecho (real). Porque la muerte no es sólo la ausencia de vida, es mucho más que eso, especialmente para nosotros. La necesidad de una muerte simbólica es necesaria para la gente. Lacan definía la muerte simbólica como una narrativa de cierre, como la sentencia final que uno debe murmurar para dejar ir a los muertos. Si cada cultura en el planeta respeta algún tipo de rito funerario es precisamente por eso. La muerte real llega naturalmente cuando el corazón deja de latir, pero la muerte simbólica es algo cultural, algo que depende del individuo y de su capacidad para lidiar con la pérdida. Aceptar la muerte significa ser capaces de escribir ese epitafio en nuestras cabezas, ser capaces de entender la vida de alguien y asumir su final.

Así que considero que Elle es una chica especialmente valiente porque aunque escucha a otros hablar sobre ella como si estuviera muerta, se rehúsa a creer que este es el fin. ¿Puede su consciencia regresar a su cuerpo? Nadie lo sabe, sólo hay una certeza... si la gente que intentó matarla ha fallado, entonces no tardarán mucho en encontrarla una segunda vez. Nuevamente, Image nos presenta una prometedora serie con el arte absolutamente grandioso de Rodin Esquejo y vibrantes colores Sonia Oback. Y también deberíamos admirar el fantástico logo diseñado por Michael Lapinski (que además de ser mi amigo en la página de Bendis también ha colaborado, al igual que yo, en The Gathering en varias ocasiones). "Mind the Gap" es realmente recomendable.