If we question the authenticity of a widely popular book, does that take merit from the work itself? The word apocrypha carries some negative connotations: false, spurious and even heretical. But when we talk about literature, can anything be defined as heretical? In any case, when Eclipse Comics editor Catherine Yronwode decided to publish Miracleman: Apocrypha, I’m quite certain that she knew exactly what she was in doing in choosing that specific word.

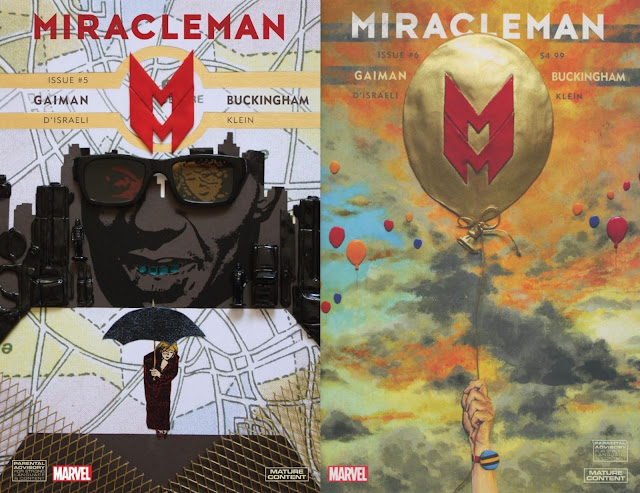

The first issue of this miniseries was released in November, 1991. Shortly after Miracleman # 22, the conclusion of Neil Gaiman and Mark Buckingham’s Golden Age arc. So this miniseries, in many ways, serves as an intermission between the end of the Golden Age and the beginning of the Silver Age, which in the end never happened. Curiously, when Marvel reprinted Alan Moore’s Miracleman, a promise was made. The Silver Age would finally see the light of day; however, that didn’t happen either. It’d be safe to assume that Marvel will never reprint the Apocrypha miniseries, since it could be even more controversial than Alan Moore and Neil Gaiman’s Miracleman series.

The opening story is “The Library of Olympus”, written by Neil Gaiman and illustrated by Mark Buckingham. In his search for perfection, Miracleman has long stopped being a superhero and he has fully embraced his divine condition. From the heights of Olympus, he rules mankind, in a relaxed and condescending way that no one could consider as tyrannical. For Miracleman, people have become strange abstractions that he can barely understand, so in an attempt to learn about normal people, he decides to nurture himself with fiction. Instead of novels or short stories, he chooses that unique form of art that we’ve come to know as comic books: “Idly, as if I do not care, I take three of them from the racks. From each garish cover a crude drawing of my face stares up at me”.

“Miracleman and the Magic Pen” is the first comic book read by Miracleman, and it’s the kind of classic story that could have come from the Mick Anglo era. Steve Moore, the writer, combines the sensibilities of yesteryear with the philosophical nature of Miracleman; indeed, the limits between reality and fiction can be easily broken. Stan Woch, who had collaborated with Alan Moore in Swamp Thing, does a magnificent job penciling and inking this story.

James Robinson writes a very violent story that would be virtually impossible to publish nowadays. “The Rascal Prince” revolves around Johnny Bates, who in Alan Moore’s run was Miracleman’s nemesis. Kelley Jones, an artist often associated with horror and darkness, magnificently captures the sinister side of Johnny Bates, who once had been Miracleman’s sidekick. Johnny has all the power he needs to conquer the world, but he uses that power to rape an innocent girl. This is the beginning of the transformation for Johnny Bates, who would end up becoming the most cruel and depraved man, and certainly the only one powerful enough to defeat Miracleman.

Sara Byam writes “The Scrapbook”, with pencils and inks by the legendary Norm Breyfogle. The story takes place in an alternative timeline, in which Miracleman decided to stay with Liz. Together, they embark upon a road trip through the US. The main conflict here is the idea of a superhuman being such as Miracleman trying to adapt to an ordinary life, but no matter how much tries, his romantic relationship with Liz is still doomed. Finally, Matt Wagner’s “Limbo” is a peculiar conversation between Miracleman and the immortal Mort. In this remarkable first issue, we get to see astonishing work from some of the best writers and artists of the time.

________________________________________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Si cuestionamos la autenticidad de un libro ampliamente popular, ¿tiene eso algún mérito en el trabajo mismo? La palabra ‘apócrifo’ tiene algunas connotaciones negativas: falso, espurio e incluso herético. Pero cuando hablamos de literatura, ¿se puede definir algo como herético? En cualquier caso, cuando Catherine Yronwode, la editora de Eclipse Comics, decidió publicar Miracleman: Apocrypha, estoy bastante seguro de que sabía exactamente lo que estaba haciendo al elegir esa palabra específica.

El primer número de esta miniserie salió en noviembre de 1991. Poco después de Miracleman # 22, la conclusión del arco argumental de la Edad de Oro de Neil Gaiman y Mark Buckingham. Entonces, esta miniserie, en muchos sentidos, sirve como un intermedio entre el final de la Edad de Oro y el comienzo de la Edad de Plata, que al final nunca sucedió. Curiosamente, cuando Marvel reimprimió Miracleman de Alan Moore, se hizo una promesa. La Edad de Plata finalmente vería la luz del día; sin embargo, esto tampoco sucedió. Sería seguro asumir que Marvel nunca reimprimirá la miniserie Apocrypha, ya que podría ser incluso más controversial que el Miracleman de Alan Moore y Neil Gaiman.

La historia inicial es “La biblioteca del Olimpo”, escrita por Neil Gaiman e ilustrado por Mark Buckingham. En su búsqueda de la perfección, Miracleman ha dejado de ser un superhéroe y ha aceptado completamente su condición divina. Desde las alturas del Olimpo, gobierna a la humanidad, de una manera relajada y condescendiente que nadie podría considerar tiránica. Para Miracleman, las personas se han convertido en extrañas abstracciones que apenas puede comprender, por lo que en un intento por aprender sobre la gente normal, decide nutrirse de la ficción. En lugar de novelas o cuentos, elige esa forma de arte única que hemos llegado a conocer como cómics: “Ociosamente, como si no me importara, saco tres de los estantes. Desde cada portada chillona me mira fijamente un tosco dibujo de mi rostro ”.

"Miracleman y el bolígrafo mágico" es el primer cómic leído por Miracleman, y es el tipo de historia clásica que podría provenir de la era de Mick Anglo. Steve Moore, el escritor, combina la sensibilidad de antaño con la naturaleza filosófica de Miracleman; de hecho, los límites entre la realidad y la ficción pueden romperse fácilmente. Stan Woch, que había colaborado con Alan Moore en Swamp Thing, hace un trabajo magnífico dibujando y entintando esta historia.

James Robinson escribe una historia muy violenta que hoy en día sería prácticamente imposible de publicar. "El príncipe granuja" gira en torno a Johnny Bates, quien en la etapa de Alan Moore fue el némesis de Miracleman. Kelley Jones, un artista asociado a menudo con el horror y la oscuridad, captura magníficamente el lado siniestro de Johnny Bates, quien alguna vez fue el compañero de Miracleman. Johnny tiene todo el poder que necesita para conquistar el mundo, y usa ese poder para violar a una chica inocente. Este es el comienzo de la transformación de Johnny Bates, quien terminaría convirtiéndose en el hombre más cruel y depravado, y ciertamente el único lo suficientemente poderoso como para derrotar a Miracleman.

Sara Byam escribe “El libro de recortes”, con lápices y tintas del legendario Norm Breyfogle. La historia se desarrolla en una línea temporal alternativa, en la que Miracleman decidió quedarse con Liz. Juntos se embarcan en un viaje por carretera por Estados Unidos. El principal conflicto aquí es la idea de un ser sobrehumano como Miracleman tratando de adaptarse a una vida ordinaria, pero no importa cuánto lo intente, su relación romántica con Liz todavía está condenada al fracaso. Finalmente, "Limbo" de Matt Wagner es una conversación peculiar entre Miracleman y el inmortal Mort. En este notable primer número, vemos el impactante trabajo de algunos de los mejores escritores y artistas de la época.