|

| Tim Bradstreet (cover / portada) |

Certainly, violence in the past would always serve some sort of purpose. But what we have seen in American high schools seems to defy reason. Is there even a semblance of purpose in the act of killing others and then committing suicide? Or isn’t it rather an emphasis on purposelessness, on unrestrained hatred, on irrationality at its worst?

When Warren Ellis started writing Hellblazer, he probably asked himself the same questions. The killing spree in schools had increased from the 80s to the 90s, and in 1998, Warren decided that it was time to take John Constantine away from his usual fracas with demons and supernatural menaces to tackle on a very real situation.

As Penny Carnes investigates the shocking child-on-child slayings and prepares a report for a Senate hearing, she soon feels frustrated. There are no answers, no motives: nothing can explain this unprecedented manifestation of violence. Why is it that in 1995, a 16 year turns into a homicide and then kills himself in Blackville-Hilda High School? Why is it that every year there are more similar cases? Penny Carnes has no answers, but John Constantine does.

|

| High school student kills a classmate and then commits suicide / un estudiante de secundaria mata a otro alumno y luego se suicida |

Ellis wrote SHOOT just before the Columbine massacre and back then DC / Vertigo editors decided it was too strong a story to be published, even though Phil Jimenez had already illustrated the story. A decade later, this decision was reversed and SHOOT finally saw the light of day after 10 years of censorship. And I applaud Vertigo for finally publishing it because I consider SHOOT one of the best standalone issues I’ve read in my life.

Certainly everyone remembers the Columbine massacre (July 1999), in which two teenagers were responsible for the deaths of 15 people before ending their own lives. The same happened in the Red Lake massacre in 2005, in which an underage student killed 8 people before committing suicide or in the Red Lion Area Junior High School shooting (the shooter was 14, the MO was the same, killing others and then killing himself) and so on. A few years ago, Michael Moore tried to share with the public some of his insights in “Bowling for Columbine” a documentary that focused on gun legislations, the National Rifle Association and the inherent violence in the American way of life.

Warren Ellis also analyzes the arguments brought on by the media at the time. Everyone needed someone or something to blame. For some, allegedly Satanist musicians such as Marilyn Manson were to be blamed, for others it was computer games or horror movies. Penny Carnes tries to come up with an answer. She hopes that she can identify the problem and get rid of it. But she can’t. That’s when Constantine shows up and explains to her that there isn’t a magical solution. This isn’t a situation that can be fixed as quickly and as efficiently as the US senate demands.

|

| researching child-on-child slayings / investigando asesinatos entre chicos |

For John Constantine the problem lies deep within us, as a culture. Just like Gus Van Sant proves in his magnificent film “Elephant”, today it’s easier to buy a gun and bullets than to find the opportunity to kiss someone else. One of the most unforgettable moments in “Elephant” takes place when the two soon-to-be killers confess to each other that they are virgins and have never even kissed anyone, and yet, they’re ready to kill others and then kill themselves (just as it happened in the Columbine massacre).

As Constantine explains, ours is “a world where kids actually go to special classes to learn to recognize real emotions and body language because they were raised by the television”. I would add that after 10 years, we have found even more ways to replace human interaction with technology. Nowadays, people are obsessed with pages like Facebook, which is nothing more than an attempt to fill in an existential void, but substituting relationships for hundreds of “friends” and “likes” doesn’t improve one’s life. Isolation, lack of emotions and selfishness seem to be the guidelines of the 21st century.

When I read SHOOT two years ago my heart stopped for a minute in the last 3 pages. There is an extremely dramatic moment that ultimately explodes in the last frame. Warren Ellis makes you feel as if someone had died in front of your eyes. You feel what the high school kid about to die is feeling, and it is a horrendous realization. For an instant, you lose faith in humankind. And then, as you put the book away, you start thinking about all the horrible and unexplainable things that happen in real life. And you realize that even if none of that makes sense, you can still cling to your feelings, break out of your isolation and start caring a little bit more about the world around you.

___________________________________________________________________________________

___________________________________________________________________________________

|

| Why school shootings are so frequent in the US? / ¿Por qué las matanzas en colegios son tan comunes en USA? |

Ciertamente, la violencia en el pasado siempre habría tenido algún tipo de propósito. Pero lo que hemos visto en las secundarias norteamericanas desafía la razón. ¿Hay al menos algún rastro de propósito en el acto de matar a otros y luego suicidarse? ¿O no es esto, más bien, un énfasis en el despropósito, en el odio desatado, en el peor tipo de irracionalidad?

Cuando Warren Ellis empezó a escribir Hellblazer, probablemente se planteó las mismas preguntas. La ola de asesinatos en los colegios había aumentado desde los 80 hasta los 90, y en 1998, Warren decidió que era momento de apartar a John Constantine de sus habituales escaramuzas con demonios y amenazas sobrenaturales para abordar una situación muy real.

Mientras Penny Carnes investiga los impactantes asesinatos entre chicos y prepara su reporte para una audiencia del senado, se siente frustrada. No hay respuestas ni motivos: nada puede explicar esta manifestación de violencia sin precedentes. ¿Por qué en 1995, un estudiante de 16 años se convierte en un homicida que luego acaba con su vida en Blackville-Hilda High School? ¿Por qué cada año hay más casos similares? Penny Carnes no tiene respuestas, pero John Constantine sí las tiene.

Ellis escribió “Shoot” justo antes de la masacre de Columbine y en ese entones los editores de DC / Vertigo decidieron que la historia era demasiado fuerte para ser publicada, incluso aunque Phil Jimenez ya había terminado de ilustrarla. Una década después, esta decisión fue revertida y "Shoot" salió a la luz luego de años de censura. Y aplaudo a Vertigo por publicarla finalmente porque considero que "Shoot" es una de las mejores historias autoconclusivas que he leído en mi vida.

|

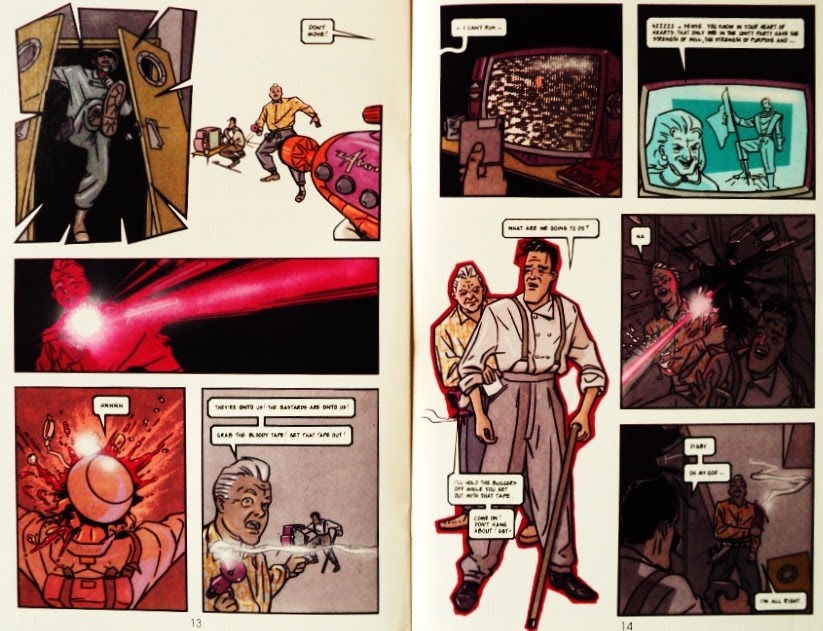

| John Constantine & Penny Carnes |

Ciertamente, todos recordarán la masacre de Columbine (julio de 1999), en la que dos adolescentes fueron responsables de las muertes de 15 personas antes de acabar con sus propias vidas. Lo mismo sucedió en la masacre de Red Lake el 2005, en la que un estudiante menor de edad mató a 8 personas antes de cometer suicidio o en la matanza de Red Lion Area Junior High School (el culpable tenía 14 años y luego de causar las muertes de otros termina suicidándose), y así sucesivamente. Hace algunos años, Michael Moore intentó compartir con el público su punto de vista en “Bowling for Columbine” un documental que se enfocaba en la legislación sobre armas, la Asociación Nacional del Rifle y la violencia inherente al estilo de vida norteamericano.

Warren Ellis también analiza los argumentos de los medios en ese momento. Todos necesitaban a alguien o algo que culpar. Para algunos, la culpa recaía en cantantes supuestamente satánicos como Marilyn Manson, para otros en los juegos de computadora o las películas de terror. Penny Carnes intenta encontrar una respuesta. Su esperanza es identificar el problema para poder eliminarlo. Pero no puede. Entonces Constantine aparece y le explica que no hay una solución mágica. Esta no es una situación que puede ser arreglada rápida y eficientemente, como exige el senado.

Para John Constantine el problema está en nosotros, en nuestra cultura. Tal como lo demuestra Gus Van Sant en su magnífico film “Elephant”, hoy en día es más fácil comprar armas y balas que encontrar la oportunidad para besar a alguien. Uno de los más inolvidables momentos de "Elephant" sucede cuando los dos futuros homicidas se confiesan mutuamente que son vírgenes y que ni siquiera han besado a alguien, y no obstante, están preparados para matar a otros y luego matarse a sí mismos (como sucedió en la masacre de Columbine).

Constantine explica que el nuestro es "un mundo en el que los chicos necesitan ir a clases especiales para aprender a reconocer emociones reales y el lenguaje corporal porque han sido educados por un televisor". Agregaría que, 10 años después, hemos encontrado incluso más maneras de reemplazar la interacción humana con tecnología. Actualmente, la gente se obsesiona por páginas como Facebook, que no es otra cosa que un intento por llenar el vacío existencial, pero sustituir relaciones con centenares de "amigos" o "me gusta" no le mejora la vida a nadie. El aislamiento, la ausencia de emociones y el egoísmo parecen definir al siglo XXI.

Cuando leí "Shoot" hace dos años mi corazón se detuvo por un minuto en las últimas 3 páginas. Hay un momento extremadamente dramático que estalla magistralmente en la última viñeta. Warren Ellis te hace sentir como si alguien hubiese muerto frente a ti. Y sientes lo que está sintiendo el chiquillo de secundaria a punto de morir, y la sensación es horrenda. Por un instante, pierdes la fe en la humanidad. Y luego, cuando sueltas el cómic, empiezas a pensar en todas las cosas horribles e inexplicables que suceden en la vida real. Y te das cuenta que aunque no tengan sentido, todavía puedes aferrarte a tus sentimientos, salir de tu aislamiento y empezar a querer un poco más el mundo que te rodea.