|

| Not a mainstream Doryphoros |

I’ve never bought a database program. Amazing coincidence (or comic addicts think alike) but I shared with a few friends pretty much the same database concept. This is how I keep tabs on my collection: I have name of the series (2000 AD is the first thing you are going to find, I like to do things alphabetically), number (I have a couple of hundreds comics from Spain, so I add another line to keep track of the different numbering), cover date (obviously no one is going to have the patience to figure out when exactly a comic book has been published), publisher, title of the story, I also write if it is the first edition or second edition, then Writer, Penciller, Inker, Colorist, Cover Artist, periodicity (mini, ongoing, one-shot, OGN, etc), language (I have comic books in Spanish).

|

| Por el amor de Hirst |

And instead of notes I have something I like to call Comments (basically I write the same thing you would usually find in the solicitation texts, e.g.: “Juston Seyfert is about to make a discovery that will change his life: the ravaged remains of a giant robot buried in his family's salvage yard! But what could a downtrodden, disillusioned high school sophomore possibly do with a 30-foot tall engine of destruction? Anything he wants!”; and if I am especially inspired I write a little something about the issue, of course nothing as elaborate as the stuff I write for the blog).

And that’s it. It took me a while to start doing this but now to update it is very quick. I love to reread too, the oldest comics in my collection have been read like twenty times, but the newest ones only two or three times.

________________________________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________________________________

|

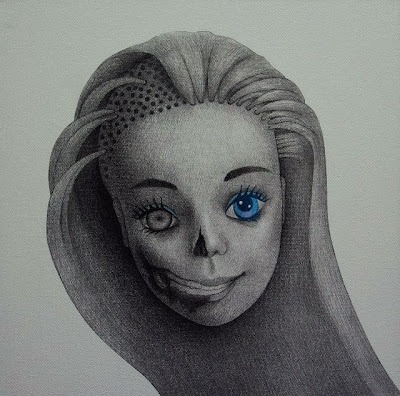

| The walking Barbie |

La primera vez que vi un cuadro de Akira Chinen fue en la Galería Shock, se trataba de uno de sus famosos “muchachos orientalizados” (término acuñado por mi amigo Iván Fernández Dávila). Un joven, en efecto, de rasgos orientales, silueta esbelta y torso desnudo que, ensordecido por un par de audífonos nos encaraba a nosotros –los espectadores– con una mirada desafecta, casi fría, mientras no apuntaba con una pistola. Curiosamente, una flecha señalaba sus oídos y otra, más sutil, partía de sus caderas, en dirección a alguna región ignota ubicada algunos palmos más abajo del ombligo. El cuadro me impresionó muchísimo, y aunque busqué el nombre del autor no lo encontré por ninguna parte. Pregunté a los galeristas y ninguno supo darme razón. Asumo que, al tratarse de una galería que recién abría sus puertas, todo estaba todavía en proceso de (des)organización. Sin embargo, en el transcurso de las semanas mis pesquisas dieron resultado. El artista de ese cuadro que tanto me había gustado era Akira Chinen. Por cierto, tuve la oportunidad de tomarle una foto al cuadro en cuestión y lo pueden ver haciendo click aquí.

Han pasado un par de años desde que la Galería Shock cerró sus puertas para siempre, pero si no fuera por ese espacio barranquino yo no hubiera conocido a Akira. O quizás sí. Al fin y al cabo, él y yo hemos coincidido con frecuencia en diversas galerías, y tenemos muchos amigos en común, y todos ellos (Iván Fernández Dávila, Elizabeth López, Eduardo Deza, José Luis Carranza, John Chauca, etc.) asistieron puntualmente a la inauguración de “Espacio y forma”, la magnífica muestra individual de Akira en la Sala 770 del Centro Cultural Ricardo Palma.

|

| my drawing: final version / mi dibujo: versión final |

Yo también estuve allí, claro, aunque no tan puntal como los demás. Y nuevamente, como en el 2011, volví a sentir esa intensidad, ese embelesamiento y ese goce intelectual frente a los cuadros de Akira. Desde aquellos de gran formato y colores sólidos, hasta la genial serie de cabezas, que se compone de 20 cuadros en formato pequeño en los que el artista nos deslumbre con su creatividad. Se trata de una propuesta muy ingeniosa, que incorpora elementos de la contemporaneidad al clasicismo del canon artístico (ese es el caso, por ejemplo, de “Not a mainstream Doryphoros”, en el que el epítome de la belleza masculina de la Grecia Antigua adquiere un aire desconsoladamente ‘fashion’ y postmoderno), que se burla abiertamente de la comercialización excesiva que domina al mundo de las galerías (así, nos ofrece “Por el amor de Hirst”, una suerte de sátira visual del famoso cráneo con incrustaciones de diamantes de Damien Hirst, artista británico amado y odiado, siempre polémico, y multimillonario) y que reelabora los referentes de la cultura pop, combinándolos magistralmente en divertidas y subversivas imágenes (“The walking Barbie” es un ejemplo idóneo, aquí la muñeca tan codiciada por las niñas se convierte en una muñeca-zombie, con la mitad del rostro putrefacto). El amor por los detalles, el trabajo minucioso y la belleza de la obra de Akira Chinen han superado mis expectativas.