So, if you were interested in having a career in the comics industry, in the 80s, you probably had two alternatives ahead of you: either doing superhero comics for DC or doing the same for Marvel. But you should never underestimate creative individuals because they’ll always find new possibilities, new outlets for their creations… just like Dave Sim did, when he decided to self-publish his magnum opus “Cerebus”. In 1985, Dave Sim met Stephen Murphy and Michael Zulli. Despite their inexperience, Sim immediately recognized their talent. And looking at the first pages of The Puma Blues, I don’t think any reasonable editor would have rejected Zulli’s art. In his foreword, Dave Sim explains why he was so interested in Michael Zulli: “Michael’s style was heavily influenced by Barry Windsor-Smith, but it was a really unique, pen-dominant take on BWS. And it was ‘current BWS’. Like me, Michael obviously thought BWS got better and better the further along he went”.

Zulli was also the main reason behind my decision for purchasing Dover’s omnibus edition, a deluxe hardcover with almost 600 pages of the most spectacular and beautiful art I’ve seen in a long time. I respect Zulli as an artist, I always have. Having read about his life and his decisions, I know he is one of the very few artists that will sacrifice the certainty of a monthly paycheck in order to preserve the integrity of his vision. So it makes perfect sense that he would put so much energy and effort into The Puma Blues, a very experimental project, and a most decidedly noncommercial venture.

|

| Gavia Immer |

Indeed, Dave Sim explains that “The whole exercise from Day One was an experiment in ethical conduct on the uneasy borderline between art and commerce”. In the first chapters of The Puma Blues (originally published in single issues by Aardvark One International / Aardvark-Vanaheim, starting in 1986), Murphy and Zulli boldly defied established rules of narrative, discarding the classic cliffhangers or the usual plot developments.

In many ways, The Puma Blues is similar to Michael Zulli’s brilliant graphic novel Fracture of the Universal Boy. Both works are an example of artistic commitment; and as experimental as they might be, they open new frontiers, while teaching us the importance of being faithful to our vision. As an independent creator, I should say that The Puma Blues is also an inspiration, it’s tangible evidence that sometimes we can do the things we want to do the most and, above all, that we can survive in this world without succumbing to the pressure of being financially viable, whatever that means.

In the epilogue, Stephen R. Bissette highlights the connections between autobiography and fiction. Gavia Immer, the protagonist, is a confused young man who is trying to come to terms with the world around him. “Twenty-one years of age and I hadn’t the least insight into what the fuck I wanted to do with my life”, affirms Gavia. A statement many of us could relate to. Personally, I know I was a bit lost when I was 21, and although it was clear to me that comics were my greatest passion, I wasn’t sure if I’d be able to make a living as a writer (even today I’m still unsure about it).

|

| Brooklyn |

|

| Human science versus nature / ciencia humana versus naturaleza |

|

| the beauty of nature / la belleza de lo natural |

According to Bissette’s afterword “Puma Blues was an idiosyncratic, singular work. Michael’s rich, illustrative art and strong sense of visual narrative composition and momentum complemented Steve’s grave, often enigmatic, scripts perfectly”. It’s amazing to observe how quickly Zulli evolved as an artist, although his style is consistent since the beginning, we can identify the moments in which his lush brushwork becomes even more refined and stunning. “1986-88 was a different era. We were, many of us, very different people, some of us at the peak of our game in terms of creating comics […] We were all younger men then, and full of ideals, and hungry in ways that only young creative people know that peculiar hunger”. There was a need to break boundaries, an urge to go to places forbidden by mainstream publishers. All this is more than evident in the pages of The Puma Blues.

“Puma Blues flew so steadily beneath the pop cultural radar, consigned to that strange limbo in which so many visionary works malinger in”, elucidates Bissette. Just like Gaiman said once, being a writer is often like being a castaway, marooned in an island, sending messages in bottles waiting to hear back from some anonymous reader, anyone, who might have found the bottle, opened it and read its content. At least, that’s the way all writers begin. And I can definitely relate to that.

The Puma Blues series was suspended before Murphy could write a proper ending. Luckily for us, almost 30 years later, Murphy and Zulli at last had the chance to finish their odyssey. In the coda, Gavia Immer grows old and suffers the consequences of contamination. An old activist, now he can barely keep up with the losses of nature. In the final chapter, Murphy relies on the impact of real information. A list of disappeared animal species, ecological catastrophes, environmental facts. This apparent neutrality makes it even more shocking for the reader. The heartbreaking ending reminded me of Imre Kertész novel “Fatelessness”, for its succinctness and verisimilitude.

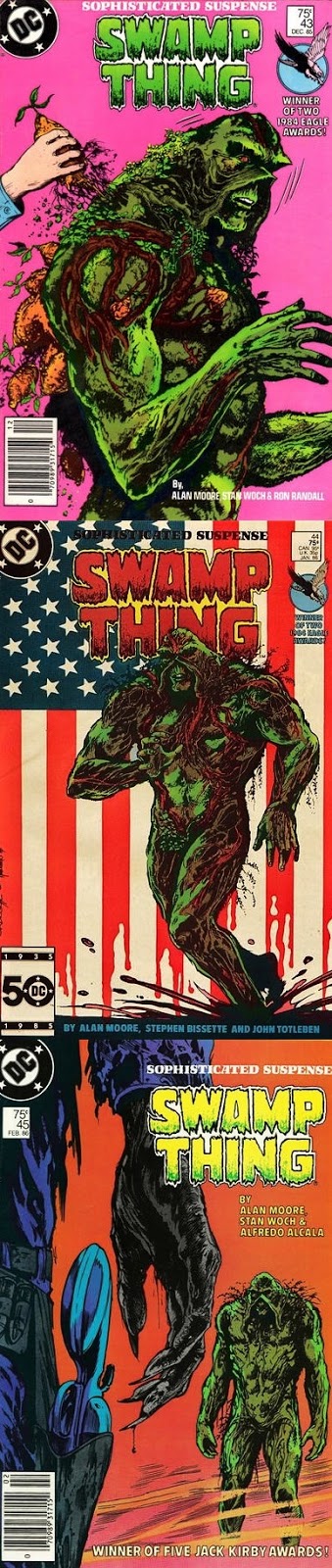

Finally, this volume also includes “Act of Faith”, a short story written by Alan Moore and illustrated by Stephen R. Bissette. In the words of Bissette, it’s “Alan’s powerful meditations on the natures of sex and love in their most primal forms”. An extraordinary and very dramatic –and quite erotic– story that takes place in only 4 pages. It is my sincere hope that, after so many years, a new generation of readers will be interested in picking up The Puma Blues. It’s the kind of honest, mature and intelligent work that only the best storytellers could accomplish, in this or any other artistic medium.

________________________________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________________________________

La vida no es fácil. Eso es algo que todos sabemos. Y especialmente para los creadores, la vida puede ser bastante difícil. No hay reglas talladas en piedra que aborden la creatividad, no hay salvavidas y, ciertamente, no hay garantías. Crearás lo que sea que vayas a crear -arte, novelas, cómics, canciones, películas- y esperarás, con todo tu corazón, que alguien por ahí te preste atención.

|

| Running away from death / escapando de la muerte |

Entonces, si hubiesen estado interesados en una carrera en la industria del cómic, en los 80s, es probable que tuvieran dos alternativas: hacer cómics de superhéroes en DC o hacer lo mismo en Marvel. Pero nunca deberíamos subestimar a los individuos creativos porque siempre encontrarán nuevas posibilidades, nuevas formas de expresar sus ideas... como hizo Dave Sim, cuando decidió auto-publicar “Cerebus”, su magnum opus. En 1985, Dave Sim se reunió con Stephen Murphy y Michael Zulli. A pesar de la inexperiencia, Sim reconoció inmediatamente el talento de ambos. Y mirando las primeras páginas de “The Puma Blues”, no creo que ningún editor razonable hubiese rechazado el arte de Zulli. En su prólogo, Dave Sim explica por qué estaba tan interesado en Michael Zulli: “El estilo de Michael estaba fuertemente influenciado por Barry Windsor-Smith, pero era un enfoque realmente único sobre BWS, en el que dominaba la pluma. Y era 'BWS actual'. Al igual que yo, Michael obviamente pensaba que BWS mejoraba y seguía mejorando cuanto más avanzaba”.

Zulli fue también la razón principal detrás de mi decisión para adquirir la edición ómnibus de Dover, un lujoso tomo en tapa dura con casi 600 páginas del arte más espectacular y hermoso que he visto en mucho tiempo. Respeto a Zulli como artista, siempre lo he hecho. Después de leer sobre su vida y sus decisiones, sé que él es uno de los pocos artistas que sacrificaría la certeza de un cheque mensual con el fin de preservar la integridad de su visión. Así que tiene sentido que pusiese tanta energía y esfuerzo en “The Puma Blues”, un proyecto muy experimental, y una aventura decididamente no comercial.

De hecho, Dave Sim explica que "Todo el proceso desde el primer día fue un experimento en cuanto a la conducta ética en la frontera inestable entre arte y comercio". En los primeros capítulos de “The Puma Blues” (publicado originalmente por Aardvark One International / Aardvark-Vanaheim, a partir de 1986), Murphy y Zulli desafiaron valientemente las reglas establecidas de la narrativa, descartando los dramas habituales o el desarrollo tradicional de la trama.

|

| the power of sex / el poder del sexo |

En más de un sentido, “The Puma Blues” es similar a otra brillante novela gráfica de Michael Zulli Fracture of the Universal Boy. Ambas obras son un ejemplo de compromiso artístico; y al ser experimentales, nos abren nuevas fronteras, al tiempo que nos enseñan la importancia de ser fieles a nuestra visión. Como creador independiente, debo decir que “The Puma Blues” es también una fuente de inspiración, es la evidencia tangible de que a veces podemos hacer las cosas que más deseamos y, sobre todo, que podemos sobrevivir en este mundo sin sucumbir a la presión de ser financieramente viables.

En el epílogo, Stephen R. Bissette destaca las conexiones entre la autobiografía y la ficción. Gavia Immer, el protagonista, es un joven confundido que está lidiando con el mundo que lo rodea. “Veintiún años de edad y yo no tenía la menor idea de qué coño quería hacer con mi vida”, afirma Gavia. Una declaración con la que muchos de nosotros podríamos identificarnos. Personalmente, sé que yo estaba un poco perdido cuando tenía 21 años, y aunque era claro para mí que los cómics eran mi más grande pasión, no estaba seguro de poder ganarme la vida como escritor (incluso hoy aún no estoy seguro de ello).

Profundamente contemplativa y evocadora, esta ambiciosa serie se centra en preocupaciones ecológicas, pero al mismo tiempo se ocupa de los problemas de la percepción y las reglas de la realidad. Podemos encontrar algunas ideas cautivantes que salen de la boca de Gavia: “Emergí con el entendimiento de que la naturaleza es incapaz de mentir”. Por otra parte, el efecto invernadero y la posterior extinción de incontables especies de animales es una preocupación tanto para los autores como para los protagonistas. “Y juntos estamos pidiendo ser oídos ya que este es nuestro mundo. Y esta es la única existencia que tenemos”. Ciertamente, en “The Puma Blues” podemos encontrar una combinación de enfoques filosóficos y existenciales, complementados con política, religión e incluso referencias al psicoanálisis y al inconsciente colectivo de Jung.

|

| Homage to Leonardo Da Vinci / homenaje a Leonardo Da Vinci |

“Habíamos intervenido profundamente en el proceso de la naturaleza sin alcanzar un pleno conocimiento de todas las dimensiones de lo natural: sus matizadas síntesis, sus frágiles interdependencias y sus narrativas vivientes”, expresa Gavia. La complejidad de la naturaleza está magníficamente retratada por Zulli a lo largo de la serie y también hay dos capítulos silenciosos centrados exclusivamente en esa “narrativa viviente”. Por más de 40 páginas, ninguna palabra es pronunciada, y sin embargo, las páginas son intensas e impresionantemente hermosas (hay todo un capítulo centrado en el puma, sus hábitos de caza y la fauna a su alrededor, sólo los sonidos de la naturaleza pueden ser escuchados en este atípico relato). Zulli tiene la capacidad para recrear perfectamente cualquier ser humano o animal, lo que demuestra que incluso un guión sin palabras puede ser elocuente siempre y cuando el arte sea capaz de lograr el efecto deseado. Zulli nunca toma el camino más fácil. Cada elección artística que hace es una decisión consciente que implica trabajo y esfuerzo adicional. Por ejemplo, en lugar de reutilizar dibujos en ciertas escenas (una práctica muy común para los dibujantes de la era digital), él reinterpreta y re-elabora la misma imagen.

De acuerdo con el epílogo de Bissette “Puma Blues fue una obra singular, idiosincrática. El arte rico e ilustrativo de Michael y su fuerte sentido de la narrativa visual y la composición complementaban perfectamente los guiones graves, a menudo enigmáticos de Steve”. Es increíble observar lo rápido que Zulli evolucionó como artista, aunque su estilo es consistente desde el principio, podemos identificar los momentos en los que sus exuberantes pinceladas se volvieron aún más refinadas y sorprendentes. "1986-88 era una época diferente. Éramos, muchos de nosotros, personas muy diferentes, algunos de nosotros estábamos en la cima en términos de creación y cómics [...] Todos éramos hombres más jóvenes en ese entonces, y llenos de ideales, y hambrientos de una manera en la que sólo los jóvenes creativos podían conocer ese hambre peculiar”. Había una necesidad de romper los límites, un impulso de ir a los lugares prohibidos por las editoriales convencionales. Todo esto es más que evidente en las páginas de “The Puma Blues”.

|

| 4 Horsemen of the apocalypse / 4 jinetes del apocalipsis |

“Puma Blues voló tranquilamente por debajo del radar cultural pop, quedando consignado a ese extraño limbo en el que tantos visionarios se quedan atascados”, aclara Bissette. Tal como Gaiman dijo alguna vez, ser un escritor es a menudo como ser un náufrago, abandonado en una isla, enviando mensajes en botellas esperando volver a escuchar de algún lector anónimo, cualquiera, que podría haber encontrado la botella, abriéndola y leyendo su contenido. Al menos, de esa manera comienzan todos los escritores. Y definitivamente puedo identificarme con ello.

La serie Puma Blues fue suspendida antes que Murphy pudiese escribir un final apropiado. Afortunadamente para nosotros, casi 30 años después, Murphy y Zulli por fin han tenido la oportunidad de terminar su odisea. En la coda, Gavia Immer envejece y sufre las consecuencias de la contaminación. Un viejo activista, ahora apenas puede mantenerse al día en relación a las pérdidas de la naturaleza. En el capítulo final, Murphy se apoya en el impacto de la información real. Una lista de especies animales desaparecidas, catástrofes ecológicas, datos ambientales. Esta aparente neutralidad es aún más impactante para el lector. El desgarrador final me recordó la novela de Imre Kertész “Sin destino”, por su concisión y verosimilitud.

Por último, este volumen también incluye “Acto de fe”, una historia corta escrita por Alan Moore e ilustrada por Stephen R. Bissette. En palabras de Bissette, estas son las “poderosas meditaciones de Alan sobre la naturaleza del sexo y el amor en sus formas más primitivas”. Una historia extraordinaria y muy dramática -y bastante erótica- que transcurre en sólo 4 páginas. Es mi sincera esperanza que, después de tantos años, una nueva generación de lectores podrá conocer a Puma Blues. Este es el tipo de trabajo honesto, maduro e inteligente que sólo los mejores narradores pueden lograr, en este o en cualquier otro medio artístico.