The Black Hound of Vengeance is one of the best stories I’ve read in my life. Each year I update my personal Top 100 best films, but so far I have never got around to completing a list of my favorite 100 comics. Perhaps it’s relatively easy to do it with films since I can watch around 250 movies a year, which means over 2500 in a decade; but I could never read only 250 comic books a year, and so one day I will have to go through literally thousands and thousands of issues before making up my mind. Even so, without a doubt, “The Black Hound of Vengeance” (published in November 1972) would be highly ranked in my top 100.

By issue 20, Barry Windsor-Smith had more participation in the scripts than ever before, and he had even designed the lettering for the titles of this last saga. Roy Thomas has admitted that having Barry Windsor-Smith as a co-plotter was great, as the British artist had plenty of original ideas that he wanted to develop.

In the previous issue, Fafnir (Conan’s friend) is injured by an arrow and falls to the sea. So far Fafnir had survived after the Cimmerian’s attack in Shadizar when they first met, then another battle with the young barbarian and the destruction of Bal-Sagoth. Of course, a measly arrow would never be enough to actually harm this gigantic, Viking-like warrior. And it’s not the arrow that causes problem but rather the foul water that gets into the wound and infects his arm.

I remember that when I first read this story I was shocked by the image of the now armless Fafnir. In a time in which the value of man was that of the strength of his sword-arm, losing an extremity could be worse than death. But there is something else here, usually comic book heroes go through all sort of ordeals unscathed. Even if they’re not invulnerable like Superman, most heroes seem to be impervious to damage (unlike Conan who suffers and bleeds almost in every issue). This is even more evident in super-hero comic books, where ‘death’ means only ‘resurrection’ and serious injuries are a rare event. And even when something like that actually happens, a change in continuity will eliminate it (Aquaman lost his hand in Peter David’s run, but after a couple of DC reboots that’s no longer the case).

So Fafnir feels like half the man he used to be, and Conan feels helpless. There is nothing he can do for his friend except staring at him while he sleeps. "And it is those who desire the good of their friends for the friends’ sake that are most truly friends, because each loves the other for what he is, and not for any incidental quality", wrote Aristotle in "The Nichomachean Ethics". When Conan first met the Vanir he wanted to kill him, because the Vanirs have always been enemies to the Cimmerians, however, once they resolved this initial dispute, they became good friends, accepting each other for what they were. In fact, like Aristotle suggested, no incidental quality can ever change that. Conan is concerned with his friend’s sake, and even saddened by Fafnir’s words: “Ah, Conan… it’s a fool thing I’ve done… traveling halfway ‘cross the world… to die at the hand of a man I’ll never see… a man who threw blazing death from afar”.

Maturity always comes at a cost, and after 20 issues Conan has learned many lessons. Both the Vanir and the Cimmerian come from barbarian backgrounds, which means they’re not used to the lies and betrayals of civilized men, and they’re not used to fighting foes from a distance (as an archer would), thus, the injury of Fafnir is the product of the dishonorable strategies of the men of Makkalet. Balthaz convinces Conan that he can get some sort of comeuppance in the city of Makkalet, and they embark on a secret mission.

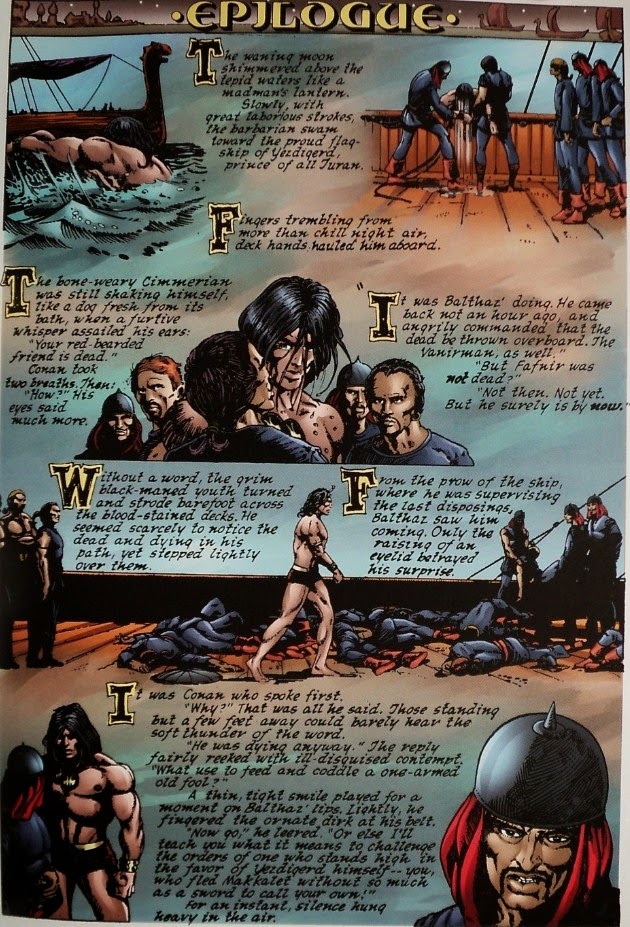

With the epilogue, paced and conceived by Barry Windsor-Smith, comes the grim and unexpected finale. After entering the sacred temple of Makkalet and barely surviving an encounter with the Black Hound, Conan discovers that his friend was thrown alive into the sea. Still alive a few hours ago, Fafnir is now gone. The cowardice of the Turanian soldiers is made evident as they could never have faced such a mighty warrior if not for his weakened condition. Everything changes for Conan in that moment. He quickly kills Balthaz, the man responsible for the death of his friend and then refuses to follow the orders of prince Yezdigerd and disfigures his face.

Now I’d like to focus on the art. The initial splash page is one of Roy Thomas favorites, and it should be ours too. The movement, the ocean tides, the sea, the Turanian soldiers, everything feels so perfectly alive in this image. An absolute master of perspective and composition, Barry Windsor-Smith creates an unforgettable moment. The second page I’m including shows the crippled Fafnir. The amazing facial expressions created by the British artist achieve a new level of excellence, just looking at all the details here leaves me in awe.

In the next page we have a great action sequence at the top, and then a magnificent view of the temple. The perspective here is quite unique and I’ve rarely found anything like it. The idea of Barry having all of this architecture in his mind and then be able to shift positions and horizon lines and make it look effortlessly is beyond impressive. In the next page we see Kharam Akkad, high priest of the city. The balance between darkness and shadows are an ideal fit for the presence of the dead soldier summoned by the high priest, we only see his skull and one eye but that’s enough to create suspense. As a wizard, Kharam Akkad has a large collection of magic mirrors, and Conan finds one that reflects not the skin but the bones beneath it. The suspense increases here and we can imagine how scared is Conan, after all, for all his skills as a warrior he he’s still a young man alone in strange land. In the next page Barry Windsor-Smith creates a room entirely covered in mirrors, and he calculates the reflections of each and every one of them. I can only imagine how long it took him to do something like that, this level of effort could never be matched by any other artist (in fact, a few issues down the road Buscema had to draw the same room and he decided to do it in a more simplistic way). The greatest irony here? In a room full of mirrors we only catch a minor glimpse of Tarim, allegedly the reason behind this war.

The battle between Conan and the Black Hound is magnificent, without any blatant supernatural elements, Barry creates a truly frightening animal. Conan barely survives this encounter, injured and exhausted he runs away. The epilogue summarizes everything I love about Barry’s art. The design of these two pages is not only original but it also flows seamlessly from panel to panel. When Conan learns the ultimate fate of Fafnir, he walks toward Balthaz: “Without a word, the grim black-maned youth turned and strode barefoot across the blood stained decks. He seemed scarcely to notice the dead and dying in his path, yet stepped lightly over them”. The young barbarian slays Balthaz with one swift movement, and Yezdigerd orders his men to kill him: “Stung into obedience by their prince’s crisp command, the soldiers moved haltingly forward. But they were slow, uncertain. And Conan was like a lion among sheep”.

Somehow, everything that has happened before becomes relevant in this last pages conceived by Barry Windsor-Smith. “The slaying of a valiant friend” was a running theme since the first issue, with the demise of Olav of the Aesirs, then in the following issues we had the deaths of Kiord, Dunlang and Taurus of Nemedia. However, all of them had been introduced and killed in less than issue, so it’s only the death of Burgun, the Gunderman that truly affects Conan. Burgun had been present for some time in Conan’s life and his departure marks the beginning of a new running theme “the death of a friend betrayed”, which reaches its peak with the loss of Fafnir.

Much in the same way that Barry reaches his maturity as an artist in these issues, fully embracing his inner voice and his true artistic style, Conan also grows up. It’s a parallel process, one deeply engraved into the heroic cosmos of the character created by Robert E. Howard and the other in the here and now of real life. Probably every critic has described the astounding artistic evolution of Barry Windsor-Smith, who changed his style not after decades or years, but only after a few weeks between one issue and the other. And the important thing is that the British artist found himself in the process, not unlike what happened to Conan, who from this point on will never have any other friend as good as Fafnir. In fact, friendship disappears after this issue, and romance starts with the coming of Red Sonja, the she-devil with a sword. But that’s a tale for another time.

________________________________________________________________________________________

"El sabueso negro de la venganza" es una de las mejores historias que he leído en mi vida. Cada año actualizo mi lista de las 100 mejores películas, pero hasta ahora nunca he completado una lista de mis 100 cómics favoritos. Tal vez es relativamente fácil hacerlo con el cine porque puedo mirar 250 películas al año, lo que significa 2500 en una década; pero nunca podría leer tan sólo 250 cómics al año, así que algún día tendré que revisar, literalmente, miles de ejemplares antes de hacer la lista. Aun así, sin lugar a dudas, "El sabueso negro de la venganza" (publicado en noviembre de 1972) estaría en un buen puesto de mi top 100.

Para el número 20, Barry Windsor-Smith tenía más participación en los guiones que antes, e incluso había diseñado las letras de los títulos en esta última saga. Roy Thomas ha admitido que tener a Barry Windsor-Smith como co-argumentista fue genial, ya que el artista británico tenía muchas ideas originales que quería desarrollar.

En el capítulo anterior, Fafnir, el amigo de Conan, cael al mar al ser herido por una flecha. Hasta ahora, Fafnir había sobrevivido al ataque del cimerio en Shadizar, luego otra batalla con el joven bárbaro y encima la destrucción de Bal-Sagoth. Por supuesto, una mísera flecha no sería suficiente para hacerle daño a este gigantesco guerrero de apariencia vikinga. Y no es la flecha la que causa problemas sino el agua sucia que se mete en la herida e infecta su brazo.

Recuerdo que cuando leí esta historia por primera vez me impactó la imagen de Fafnir sin brazo. En una época en la que el valor del hombre dependía de la habilidad con la espada, perder una extremidad podría ser peor que la muerte. Pero hay algo más, usualmente los héroes de los cómics pasan por todo tipo de hazañas y salen ilesos. Incluso si no son invulnerables como Superman, la mayoría de héroes parece inmune al daño (a diferencia de Conan, que sufre y sangra en cada número). Eso se hace más evidente en los cómics de súper-héroes, en los que la 'muerte' significa 'resurrección' y las heridas serias son un raro evento. E incluso cuando algo así sucede, un cambio en la continuidad eliminará todo (Aquaman perdió una mano en la etapa de Peter David, pero luego de un par de relanzamientos de DC es como si nada hubiera pasado).

Así que Fafnir siente que ya no es el hombre que solía ser, y Conan se siente desamparado. No hay nada que pueda hacer por su amigo excepto observarlo mientras duerme. "Y son aquellos que desean el bien de sus amigos por el bienestar de los amigos, los que son realmente amigos, porque cada uno ama al otro por lo que es, y no por una cualidad incidental", escribió Aristóteles en "Ética para Nicómaco". Cuando Conan conoció al vanir lo quiso matar, porque los vanires han sido siempre enemigos de los cimerios, sin embargo, cuando concluyó esta disputa inicial, se hicieron buenos amigos, aceptándose como eran. De hecho, como sugiere Aristóteles, ninguna cualidad incidental puede cambiar la amistad. Conan está preocupado por el bienestar de su amigo, e incluso entristecido por las palabras de Fafnir: "Ah, Conan... lo que he hecho es una necedad... viajar a través de medio mundo... para morir a manos de un hombre al que nunca veré... un hombre que, desde lejos, arrojó una muerte ardiente".

La madurez siempre tiene un costo, y después de 20 números Conan ha aprendido muchas lecciones. Ambos, el vanir y el cimerio, son bárbaros, eso significa que no están acostumbrados a las mentiras y a las traiciones de los hombres civilizados, y no están habituados a luchar contra enemigos que pelean de lejos (como los arqueros), por ello, la herida de Fafnir es el producto de la estrategia sin honor de los hombres de la capital. Balthaz convence a Conan para embarcarse en una misión secreta en la ciudad de Makkalet.

En el epílogo, planeado y concebido por Barry Windsor-Smith llega un terrible e inesperado final. Después de entrar al templo sagrado de Makkalet y sobrevivir con las justas al sabueso negro, Conan descubre que su amigo fue arrojado vivo al mar. Todavía con vida hace algunas horas, ahora Fafnir ha desaparecido para siempre. La cobardía de los soldados turanios se hace evidente, ellos no se habrían atrevido a enfrentarse al poderoso guerrero si hubiese estado en óptimas condiciones. Todo cambia para Conan en ese momento. Rápidamente mata a Balthaz, el hombre responsable de la muerte de su amigo, y luego rehúsa obedecer las órdenes del príncipe Yezdigerd y desfigura su rostro.

Me gustaría enfocarme en el arte. La página inicial es una de las favoritas de Roy Thomas, y con justo motivo. El movimiento, las olas, el mar, los soldados turanios, todo se siente tan perfectamente vivo en esta imagen. Un amo absoluto de la perspectiva y la composición, Barry Windsor-Smith crea un momento inolvidable. La segunda página que estoy incluyendo muestra a Fafnir herido. Las asombrosas expresiones faciales creadas por el artista británico alcanzan un nuevo nivel de excelencia, sólo con ver todos los detalles me quedo sin aliento.

En la siguiente página tenemos una grandiosa secuencia de acción en la parte de arriba, luego una magnífica vista del templo. La perspectiva aquí es bastante única y rara vez he encontrado algo así. Barry tenía toda esta arquitectura en su mente y era capaz de desplazar los puntos de fuga y las líneas del horizonte, como si hacerlo no requiriera mayor esfuerzo. Impresionante. En la siguiente página vemos a Kharam Akkad, el sacerdote de la ciudad. El balance entre la oscuridad y las sombras refuerzan la presencia del soldado muerto invocado por el sacerdote, sólo vemos su cráneo y un ojo, pero eso es suficiente para crear suspenso. Como hechicero, Kharam Akkad tiene una colección grande de espejos mágicos, y Conan encuentra uno que no refleja su piel sino sus huesos. El suspenso aumenta aquí, y podemos imaginar lo asustado que está Conan, después de todo, a pesar de su destreza como guerrero sigue siendo un joven solo en una tierra extraña. En la siguiente página Barry Windsor-Smith crea una habitación enteramente tapizada con espejos, y calcula los reflejos de cada uno. Sólo puedo imaginar el tiempo que le tomó hacer algo así, ningún otro artista sería capaz de este nivel de esfuerzo (de hecho, algunos números después, John Buscema dibujó de manera simplista la sala de los espejos). ¿La mayor ironía? En un cuarto lleno de espejos sólo percibimos de un vistazo a Tarim, la supuesta razón detrás de la guerra.

La batalla entre Conan y el sabueso negro es tremenda, sin elementos sobrenaturales obvios, Barry crea a un animal pavoroso. Conan apenas sobrevive este encuentro, herido y exhausto, huye. El epílogo resume todo lo que adoro del arte de Barry. El diseño de estas dos páginas no sólo es original sino que cada viñeta fluye sin problemas hacia la siguiente. Cuando Conan descubre lo que le sucedió a Fafnir, camina hacia Balthaz: "Sin una palabra, el hosco joven de melena negra giró y caminó descalzo sobre la cubierta manchada de sangre. Parecía notar apenas a los muertos y a los moribundos en su camino, aun así, sus pisadas fueron ligeras". El joven bárbaro ejecuta a Balthaz de un sólo movimiento, y Yezdigerd ordena a sus hombres que lo maten: "Aguijoneados por la obediencia a los amargos mandatos del príncipe, los soldadas avanzaron hacia adelante. Pero eran lentos, inciertos. Y Conan era como un león entre las ovejas".

De algún modo, todo lo que pasó antes se hace relevante en estas últimas páginas concebidas por Barry Windsor-Smith. "El asesinato de un amigo valiente" fue un tema recurrente desde el primer número, con la muerte de Olav, de los aesires, luego en subsecuentes capítulos murieron Kiord, Dunlang y Taurus de Nemedia. Sin embargo, todos habían llegado y perecido en un sólo número, así que sólo la muerte de Burgun, el Gunderman, afecta realmente a Conan. Burgun había estado presente en la vida de Conan por algún tiempo, y su partida marca el comienzo de un nuevo tema recurrente "la muerte de un amigo traicionado", que llega a su máximo exponente con la pérdida de Fafnir.

Del mismo modo que Barry alcanza la madurez artística en estos números, y acepta plenamente su voz interior y su verdadero estilo artístico, Conan también crece. Es un proceso paralelo, uno profundamente arraigado en el cosmos heroico del personaje creado por Robert E. Howard y el otro en el aquí y en el ahora de la vida real. Probablemente todos los críticos han descrito la increíble evolución artística de Barry Windsor-Smith, que cambió su estilo no después de décadas ni años, sino entre las semanas que separaban una entrega de Conan de la siguiente. Y lo importante es que el artista británico se encontró a sí mismo en el proceso, algo similar sucede con Conan, que a partir de esta saga nunca más tendrá un amigo tan cercano como Fafnir. De hecho, la amistad desaparecerá a partir de ahora, y empezará el romance con la llegada de Sonja la Roja, la diablesa de las espadas. Pero ese es un relato para otra ocasión.

March 28, 2012

March 27, 2012

Conan the Barbarian # 19 - Thomas & Barry Windsor-Smith

Some works of literature are unforgettable, some artistic creations are immortal. Comic books are an amazing medium because they combine literature with art, words with images, narrative outlines with visual storytelling. More often than not, one of the two prevails, we either have a very solid story with average art or an uninspired script with astonishing art. Sometimes, of course, we are lucky enough to see both elements in ideal harmony and that’s when you get a masterpiece.

The first issues of Conan the Barbarian were quite good, but as Barry Windsor-Smith followed his instincts and stopped emulating Jack ‘King’ Kirby, his artistic evolution became evident. And Roy Thomas did everything he could to be on the same level of grandeur. The collaboration between the British artist and the American writer was most fruitful, and the last issues of their Conan run are proof of it.

“Hawks from the Sea” (published in October 1972) is the first chapter of the most epic Conan saga ever. Drafted by Turanian prince Yezdigerd, Fafnir, the Vaenir, and Conan, the Cimmerian, will fight in a holy war against Makkalet.

Much has been said about the nature of religion and wars, and it’s not unusual for the two of them to be intertwined. If religion is nothing more than a veil of fantasy which precludes the subject from seeing the ‘real’, then religion will evidently and perpetually be imbricated into reality. The elusive meaning of life is supposed to become graspable if we pray to the gods and do the things we ought to do. At the same time, wars frequently follow a preordained narrative which pretends to give form to the real –the ‘real’ understood as that which predates and exceeds language- and neatly tidies it up according to whatever reality is deemed necessary at any given juncture.

In simpler words, either in religion or in war, we follow orders. We follow the dictates not of our consciousness but of our societal structures. Religions are not there to be questioned, or challenged or doubted, in the same way that generals or kings are not to be defied. So it’s not accidental that one of the most astounding Conan stories revolves around a holy war. We could easily see Conan as an individual that bears some resemblance with Lacan's inverted E, which is used in his sexuation graphic to represent "the one man not castrated". Now, obviously this doesn’t mean that the young Barbarian is surrounded by eunuchs, but rather that all of his temporary allies have fully entered into the symbolic order; castration, according to Lacan, occurs when we are fully inserted into the symbolic order. This sine qua non condition to be a part of the world also means obedience, obedience to the law of the father, to the traditions of society and to the mandates of religion.

Everyone in the Turanian army believes in the sacred Tarim, a mythic figure who saved them from the wrath of the sea of Vilayet. Their beliefs are so strong that sometimes they act as irrational zealots, but doesn’t this happen frequently even in today’s world? From the Jehovah’s witnesses that will constantly disrespect your privacy by knocking on your door to a group of men willing to hijack an airplane because they are following divine orders.

All that Conan sees is a painted wooden idol revered by everyone, and of course he feels as if this war is simply not worth his effort. Because of this heresy, Balthaz, the ship’s captain, will become his enemy. When prince Yezdigerd explains that the holy war started when the Tarim incarnate was stolen from Turan and now will only end after retrieving the Tarim and burning down Makkalet, he neglects to mention a more pedestrian truth. As Fafnir points out, Makkalet is the one and only trading rival for Turan, so the true motivation here is, after all, securing the riches of the kingdom by exterminating its competition.

In the same way religion has a way of influencing people’s behavior, war has mechanisms of its own. As Slavoj Žižek explains “Fundamentalists do what they perceive as good deeds in order to fulfill God's will and to earn salvation; atheists do them simply because it is the right thing to do. Is this also not our most elementary experience of morality? When I do a good deed, I do so not with an eye toward gaining God's favor; I do it because if I did not, I could not look at myself in the mirror. A moral deed is by definition its own reward. David Hume, a believer, made this point in a very poignant way, when he wrote that the only way to show true respect for God is to act morally while ignoring God's existence”. In real life, most believers are entirely dependent of this big Other, this deity that floats above their heads and keeps an eye over them. Heteronomous behavior is thus quite common even in the 21st century.

Not unlike religion, war also nurtures the heteronomy of men. In the same way most Nazi officers pleaded to be non-guilty by saying “they were just following orders”, soldiers are trained simply to do as they’re told, and thus any trace of autonomy ends up being eradicated. No war could take place if it couldn’t be somehow legitimized. So all wars follow certain prearranged narratives that seclude the mundane man –the common soldier- from learning the truth. Words such as patriotism and honor are part of the language of war, but they wouldn’t be so effective without a clear narrative structure. How did the war between Ilium and the Achaeans begin? We can either believe the poetic origin as explained by Homer and other Greek authors (id est the kidnapping of fair Helen by Paris) or the fact that at the dawn of the Mycenaean period, Troy -due to its geographical location- was a natural contender for the maritime supremacy of the Achaeans. What was the motivation behind the conquest of America? According to the kings of Spain, there was an imperative need to evangelize everyone in this new continent, by bringing the word of god to this exotic people, Spain was acting purely out of mercy. The royal documents emphasize this ‘good deed’ but they adequately forget to highlight the huge amount of gold obtained from the Incas or other civilizations. What was the justification for the Iraq war? Lethal weapons, nuclear arsenal, etc., the truth however became apparent: oil companies and the armament industry profited from the war more than anyone could possibly realize. So, in every war we have a justification, a story that pertains to reality, but if we have a critical mind we will discover the real beneath it all.

Conan and Fafnir are able to look right through the intentions of the men from Turan, but there’s no turning back for them. And so without much conviction, the Cimmerian and the Vaenir attack the coast of Makkalet. I have read this specific issue many times in my life. It’s hard to imagine a better way to describe a large scale war than to focus on two foreigners, two men that have other gods and other attitudes. In one issue Roy Thomas provides the reader with a profound analysis of war and religion, with a complexity and maturity that would be impossible to find 40 years later (in and outside the comic book industry). Indeed, as paradoxical as it sounds, in more recent times immaturity has become the rule when it comes to religion (only a couple of years ago we had Americans insisting on creationism being taught at schools and muslims threatening to bomb cities because of a caricature of Muhammad).

Nonetheless, this issue of Conan the Barbarian would not be the same if not for Barry Windsor-Smith’s beautiful art. The first page portrays a brooding Conan, there is a sense of heaviness around him, pencils and inks actually create real weight in this splash page. Conan sits with a grim expression, not unlike the most famous statue sculpted by Auguste Rodin “The Thinker”, which was wrongfully titled since Rodin actually conceived it as “Dante in front of the Gates of Hell”. That is the feeling we get from Conan, he’s indeed catching a glimpse of the hell that is yet to come. Because, as Sartre so aptly put it long ago “l'enfer, c'est les autres” (hell is the others).

The second page that I’m including here recounts the accomplishments of the Tarim, this foundational myth and its imagery recreate the figure of the messiah, present in so many religions. Next we have an extraordinary sequence composed by tall and narrow panels, as Conan walks towards a seagull. The peacefulness of the scene contrasts against the thoughts of the young barbarian: “Here among men called civilized, a stranger may smile and extend one hand… while the other strains furtively for the hidden dagger. Here Conan finds all motives murky… all actions devious…”. The first sight of the Turanian siege-fleet is also a powerful scene, it has the same gravitas of some of Durer’s etchings. The city of Makkalet is an architectural jewel. Barry Windsor-Smith built this city stone by stone, in an era in which no such thing as computer generated images existed; nowadays a software like sketch-up prevents artists from actually doing all the heavy lifting when it comes to drawing even a simple wall and a couple of windows. The fall of Fafnir and the final outcome of the battle are an undisputable example of the British artist’s talent. And the next issue is even better.

______________________________________________________________________________________

Algunas obras literarias son inolvidables, algunas creaciones artísticas son inmortales. Los cómics son un medio asombroso porque combinan literatura con arte, palabras con imágenes, pautas narrativas con desarrollos visuales. A menudo, uno de los dos prevalece, y tenemos o bien una historia sólida con arte regular o bien un guión poco inspirado con impresionante arte. A veces, desde luego, tenemos suerte suficiente para ver ambos elementos reunidos en armonía, y allí es cuando aparece la obra maestra.

Los primeros números de Conan el Bárbaro fueron bastante buenos, pero conforme Barry Windsor-Smith seguía sus instintos y dejaba de emular a Jack ‘King’ Kirby, su evolución artística se hizo evidente. Y Roy Thomas hizo lo posible para estar al mismo nivel de grandiosidad. La colaboración entre el artista británico y el escritor norteamericano fue sumamente fructífera, y los últimos números de Conan así lo demuestran.

"Los halcones del mar" (octubre 1972) es el primer capítulo de la saga más épica de Conan. Reclutados por el príncipe turanio Yezdigerd, Fafnir, el vanir, y Conan, el cimerio, lucharán en una guerra santa contra Makkalet.

Se ha dicho mucho sobre la naturaleza de la religión y de las guerras, y no es inusual que las dos se encuentren entrelazadas. Si la religión no es nada más que un velo de la fantasía que esconde lo 'real', entonces la religión estará, evidente y perpetuamente, imbricada en la realidad. El elusivo significado de la vida está, supuestamente, al alcance de aquellos que rezan a los dioses y hacen lo que deben hacer. Al mismo tiempo, las guerras a menudo siguen narrativas predeterminadas que pretenden darle forma a lo real -lo 'real' entendido como aquello que precede y excede al lenguaje- y ordenarlo prolijamente de acuerdo a la realidad y dependiendo de la coyuntura.

Dicho con más sencillez, ya sea en la religión o en la guerra, seguimos órdenes. Seguimos los dictados no de nuestra conciencia sino de nuestras estructuras societarias. No se puede cuestionar a las religiones, ni dudar de ellas, del mismo modo que no se puede desafiar a los generales o a los reyes. Así que no es accidental que la guerra santa sea el escenario de una de las más impactantes historias de Conan. Podríamos fácilmente identificar a Conan con la E invertida de Lacan, que se usa en su gráfico de sexuación para representar al "único hombre no castrado". Obviamente, esto no significa que el joven bárbaro está rodeado de eunucos, sino más bien que sus aliados temporales se han insertado por completo en el orden simbólico; la castración, para Lacan, ocurre cuando nos insertamos por completo en el orden simbólico. Esta condición sine qua non para ser parte del mundo también significa obediencia, obediencia a la ley del padre, a las tradiciones de la sociedad y a los mandatos de la religión.

Todos en el ejército turanio creen en el sagrado Tarim, una figura mítica que los salvó de la ira del mar de Vilayet. Sus creencias son tan fuertes que a veces actúan como fanáticos irracionales, pero ¿no sucede esto con frecuencia incluso en el mundo de hoy? Desde los testigos de Jehová que no respetan tu privacidad y tocan con frecuencia la puerta de tu casa hasta un grupo de hombres capaces de secuestrar un avión porque están siguiendo órdenes divinas.

Todo lo que Conan ve es un ídolo de madera pintada reverenciado por todos, y por supuesto siente que esta guerra no merece esfuerzo alguno de su parte. A causa de esta herejía, Balthaz, el capitán de la nave, será su enemigo. Cuando el príncipe Yezdigerd explica que la guerra santa empezó cuando el Tarim encarnado fue robado de Turan y terminará solamente cuando sea recuperado y Makkalet sea destruida, él olvida mencionar una verdad más pedestre. Como señala Fafnir, Makkalet es el único rival para el comercio de Turan, así que la verdadera motivación aquí es, después de todo, asegurar las riquezas del reino exterminando a la competencia.

Del mismo modo que la religión influye en el comportamiento de la gente, la guerra tiene mecanismos similares. Como explica Slavoj Žižek "Los fundamentalistas hacen lo que ellos perciben como buenos actos para satisfacer la voluntad de dios y para ganar la salvación; los ateos hacen buenos actos simplemente porque es lo correcto, no lo hago para ganar el favor de dios; lo hago porque si no lo hiciera, no podría mirarme en el espejo. Un acto moral es por definición su propia recompensa. David Hume, creyente, resaltó esto de modo significativo cuando escribió que la única forma de mostrar verdadero respeto a dios es actuar moralmente ignorando la existencia de dios". En la vida real, la mayoría de creyentes depende enteramente de un gran Otro, una deidad que flota sobre sus cabezas y los vigila. La actitud heterónoma es bastante común incluso en el siglo XXI.

Al igual que la religión, la guerra también nutre la heteronomía del hombre. Del mismo modo que los oficiales nazi declaraban su inocencia al decir que "sólo seguían órdenes", los soldados son entrenados para hacer lo que se les dice, erradicando así todo rastro de autonomía. Ninguna guerra podría ocurrir si no fuera legitimada de algún modo. Así es que todas las guerras siguen ciertas narrativas predeterminadas que impiden que el hombre común -el soldado de a pie- descubra la verdad. Palabras como patriotismo y honor son parte del lenguaje de la guerra, pero no serían tan efectivas sin una estructura narrativa clara. ¿Cómo empezó la guerra entre Ilión y los aqueos? Podemos creer en el origen poético descrito por Homero y otros autores griegos (es decir, el rapto de la bella Helena a manos de Paris) o el hecho de que en el inicio del periodo micénico, Troya -a causa de su ubicación geográfica- era un rival natural para la supremacía marítima de los aqueos. ¿Cuál fue la motivación detrás de la conquista de América? De acuerdo a los reyes de España, había una imperiosa necesidad de evangelizar a todos en este nuevo continente, al llevar la palabra de dios a estos pueblos exóticos, España actuaba piadosamente. Los documentos reales enfatizan esta 'buena obra' pero, convenientemente, olvidan resaltar la inmensa cantidad de oro obtenida de los incas y otras civilizaciones. ¿Cuál fue la justificación de la guerra de Irak? Armas letales, arsenal nuclear, etc., la verdad sin embargo se hizo evidente: las compañías petroleras y la industria de armamento obtuvieron fuertes ganancias con esta guerra. Así que para cada guerra hay una justificación, una historia que pertenece a la realidad, pero si tenemos una mente crítica descubriremos lo 'real' que subyace a todo esto.

Conan y Fafnir son capaces de entender las intenciones de los hombres de Turan, pero ya no hay vuelta atrás. Y sin mucha convicción, el cimerio y el vanir atacan la costa de Makkalet. He leído este cómic muchas veces en mi vida. Es difícil imaginar una mejor manera de describir una guerra a gran escala que enfocándose en dos extranjeros, dos hombres que tienen otros dioses y otras actitudes. En un sólo ejemplar, Roy Thomas proporciona una análisis profundo de la guerra y la religión, con una complejidad y madurez que son imposibles de encontrar 40 años después (dentro y fuera de la industria del cómic). De hecho, por paradójico que suene, en épocas recientes la inmadurez se ha convertido en la norma para la religión (apenas hace un par de años los norteamericanos insistían en que el creacionismo se enseñe en los colegios y los musulmanes amenazaban con bombardear ciudades a causa de una caricatura de Mohammed).

No obstante, este número de Conan el bárbaro no sería igual sin el hermoso arte de Barry Windsor-Smith. La primera página retrata a un Conan meditabundo, hay una sensación de gravedad, los lápices y las tintas logran otorgarle peso de verdad. Conan está sentado con una expresión sombría, como si fuera la famosa estatua esculpida por Auguste Rodin "El pensador", que fue llamada así erróneamente ya que Rodin de hecho la concibió como "Dante en las puertas del infierno". Ese es el sentimiento que expresa Conan, él intuye el infierno que se avecina. Porque, como Sartre dijo tan acertadamente “l'enfer, c'est les autres” (el infierno son los otros).

La segunda página que incluyo aquí es un recuento de los logros del Tarim, este mito fundacional que recrea la figura del mesías, presente en tantas religiones. Luego tenemos una extraordinaria secuencia compuesta por viñetas altas y angostas, mientras Conan camina hacia una gaviota. La paz de la escena contrasta con los pensamientos del joven bárbaro: "Aquí entre hombres llamados civilizados, un extraño puede sonreír y extender una mano... mientras la otra se cierne furtivamente sobre la daga oculta. Aquí Conan encuentra insondables todos los motivos... y arteras todas las acciones...". El primer vistazo a la flota de asedio de Turan es también una escena poderosa, tiene la misma seriedad que los grabados de Durero. La ciudad de Makkalet es una joya arquitectónica. Barry Windsor-Smith construye esta ciudad piedra por piedra, en una época la que no existían las imágenes generadas en computadoras; hoy en día, un software como sketch-up impide que los artistas hagan el trabajo pesado y dibujen una simple pared o un par de ventanas. La caída de Fafnir y el desenlace final de la batalla son ejemplos indiscutibles del talento del artista británico. Y el próximo número es todavía mejor.

The first issues of Conan the Barbarian were quite good, but as Barry Windsor-Smith followed his instincts and stopped emulating Jack ‘King’ Kirby, his artistic evolution became evident. And Roy Thomas did everything he could to be on the same level of grandeur. The collaboration between the British artist and the American writer was most fruitful, and the last issues of their Conan run are proof of it.

“Hawks from the Sea” (published in October 1972) is the first chapter of the most epic Conan saga ever. Drafted by Turanian prince Yezdigerd, Fafnir, the Vaenir, and Conan, the Cimmerian, will fight in a holy war against Makkalet.

Much has been said about the nature of religion and wars, and it’s not unusual for the two of them to be intertwined. If religion is nothing more than a veil of fantasy which precludes the subject from seeing the ‘real’, then religion will evidently and perpetually be imbricated into reality. The elusive meaning of life is supposed to become graspable if we pray to the gods and do the things we ought to do. At the same time, wars frequently follow a preordained narrative which pretends to give form to the real –the ‘real’ understood as that which predates and exceeds language- and neatly tidies it up according to whatever reality is deemed necessary at any given juncture.

In simpler words, either in religion or in war, we follow orders. We follow the dictates not of our consciousness but of our societal structures. Religions are not there to be questioned, or challenged or doubted, in the same way that generals or kings are not to be defied. So it’s not accidental that one of the most astounding Conan stories revolves around a holy war. We could easily see Conan as an individual that bears some resemblance with Lacan's inverted E, which is used in his sexuation graphic to represent "the one man not castrated". Now, obviously this doesn’t mean that the young Barbarian is surrounded by eunuchs, but rather that all of his temporary allies have fully entered into the symbolic order; castration, according to Lacan, occurs when we are fully inserted into the symbolic order. This sine qua non condition to be a part of the world also means obedience, obedience to the law of the father, to the traditions of society and to the mandates of religion.

Everyone in the Turanian army believes in the sacred Tarim, a mythic figure who saved them from the wrath of the sea of Vilayet. Their beliefs are so strong that sometimes they act as irrational zealots, but doesn’t this happen frequently even in today’s world? From the Jehovah’s witnesses that will constantly disrespect your privacy by knocking on your door to a group of men willing to hijack an airplane because they are following divine orders.

All that Conan sees is a painted wooden idol revered by everyone, and of course he feels as if this war is simply not worth his effort. Because of this heresy, Balthaz, the ship’s captain, will become his enemy. When prince Yezdigerd explains that the holy war started when the Tarim incarnate was stolen from Turan and now will only end after retrieving the Tarim and burning down Makkalet, he neglects to mention a more pedestrian truth. As Fafnir points out, Makkalet is the one and only trading rival for Turan, so the true motivation here is, after all, securing the riches of the kingdom by exterminating its competition.

In the same way religion has a way of influencing people’s behavior, war has mechanisms of its own. As Slavoj Žižek explains “Fundamentalists do what they perceive as good deeds in order to fulfill God's will and to earn salvation; atheists do them simply because it is the right thing to do. Is this also not our most elementary experience of morality? When I do a good deed, I do so not with an eye toward gaining God's favor; I do it because if I did not, I could not look at myself in the mirror. A moral deed is by definition its own reward. David Hume, a believer, made this point in a very poignant way, when he wrote that the only way to show true respect for God is to act morally while ignoring God's existence”. In real life, most believers are entirely dependent of this big Other, this deity that floats above their heads and keeps an eye over them. Heteronomous behavior is thus quite common even in the 21st century.

Not unlike religion, war also nurtures the heteronomy of men. In the same way most Nazi officers pleaded to be non-guilty by saying “they were just following orders”, soldiers are trained simply to do as they’re told, and thus any trace of autonomy ends up being eradicated. No war could take place if it couldn’t be somehow legitimized. So all wars follow certain prearranged narratives that seclude the mundane man –the common soldier- from learning the truth. Words such as patriotism and honor are part of the language of war, but they wouldn’t be so effective without a clear narrative structure. How did the war between Ilium and the Achaeans begin? We can either believe the poetic origin as explained by Homer and other Greek authors (id est the kidnapping of fair Helen by Paris) or the fact that at the dawn of the Mycenaean period, Troy -due to its geographical location- was a natural contender for the maritime supremacy of the Achaeans. What was the motivation behind the conquest of America? According to the kings of Spain, there was an imperative need to evangelize everyone in this new continent, by bringing the word of god to this exotic people, Spain was acting purely out of mercy. The royal documents emphasize this ‘good deed’ but they adequately forget to highlight the huge amount of gold obtained from the Incas or other civilizations. What was the justification for the Iraq war? Lethal weapons, nuclear arsenal, etc., the truth however became apparent: oil companies and the armament industry profited from the war more than anyone could possibly realize. So, in every war we have a justification, a story that pertains to reality, but if we have a critical mind we will discover the real beneath it all.

Conan and Fafnir are able to look right through the intentions of the men from Turan, but there’s no turning back for them. And so without much conviction, the Cimmerian and the Vaenir attack the coast of Makkalet. I have read this specific issue many times in my life. It’s hard to imagine a better way to describe a large scale war than to focus on two foreigners, two men that have other gods and other attitudes. In one issue Roy Thomas provides the reader with a profound analysis of war and religion, with a complexity and maturity that would be impossible to find 40 years later (in and outside the comic book industry). Indeed, as paradoxical as it sounds, in more recent times immaturity has become the rule when it comes to religion (only a couple of years ago we had Americans insisting on creationism being taught at schools and muslims threatening to bomb cities because of a caricature of Muhammad).

Nonetheless, this issue of Conan the Barbarian would not be the same if not for Barry Windsor-Smith’s beautiful art. The first page portrays a brooding Conan, there is a sense of heaviness around him, pencils and inks actually create real weight in this splash page. Conan sits with a grim expression, not unlike the most famous statue sculpted by Auguste Rodin “The Thinker”, which was wrongfully titled since Rodin actually conceived it as “Dante in front of the Gates of Hell”. That is the feeling we get from Conan, he’s indeed catching a glimpse of the hell that is yet to come. Because, as Sartre so aptly put it long ago “l'enfer, c'est les autres” (hell is the others).

The second page that I’m including here recounts the accomplishments of the Tarim, this foundational myth and its imagery recreate the figure of the messiah, present in so many religions. Next we have an extraordinary sequence composed by tall and narrow panels, as Conan walks towards a seagull. The peacefulness of the scene contrasts against the thoughts of the young barbarian: “Here among men called civilized, a stranger may smile and extend one hand… while the other strains furtively for the hidden dagger. Here Conan finds all motives murky… all actions devious…”. The first sight of the Turanian siege-fleet is also a powerful scene, it has the same gravitas of some of Durer’s etchings. The city of Makkalet is an architectural jewel. Barry Windsor-Smith built this city stone by stone, in an era in which no such thing as computer generated images existed; nowadays a software like sketch-up prevents artists from actually doing all the heavy lifting when it comes to drawing even a simple wall and a couple of windows. The fall of Fafnir and the final outcome of the battle are an undisputable example of the British artist’s talent. And the next issue is even better.

______________________________________________________________________________________

Algunas obras literarias son inolvidables, algunas creaciones artísticas son inmortales. Los cómics son un medio asombroso porque combinan literatura con arte, palabras con imágenes, pautas narrativas con desarrollos visuales. A menudo, uno de los dos prevalece, y tenemos o bien una historia sólida con arte regular o bien un guión poco inspirado con impresionante arte. A veces, desde luego, tenemos suerte suficiente para ver ambos elementos reunidos en armonía, y allí es cuando aparece la obra maestra.

Los primeros números de Conan el Bárbaro fueron bastante buenos, pero conforme Barry Windsor-Smith seguía sus instintos y dejaba de emular a Jack ‘King’ Kirby, su evolución artística se hizo evidente. Y Roy Thomas hizo lo posible para estar al mismo nivel de grandiosidad. La colaboración entre el artista británico y el escritor norteamericano fue sumamente fructífera, y los últimos números de Conan así lo demuestran.

"Los halcones del mar" (octubre 1972) es el primer capítulo de la saga más épica de Conan. Reclutados por el príncipe turanio Yezdigerd, Fafnir, el vanir, y Conan, el cimerio, lucharán en una guerra santa contra Makkalet.

Se ha dicho mucho sobre la naturaleza de la religión y de las guerras, y no es inusual que las dos se encuentren entrelazadas. Si la religión no es nada más que un velo de la fantasía que esconde lo 'real', entonces la religión estará, evidente y perpetuamente, imbricada en la realidad. El elusivo significado de la vida está, supuestamente, al alcance de aquellos que rezan a los dioses y hacen lo que deben hacer. Al mismo tiempo, las guerras a menudo siguen narrativas predeterminadas que pretenden darle forma a lo real -lo 'real' entendido como aquello que precede y excede al lenguaje- y ordenarlo prolijamente de acuerdo a la realidad y dependiendo de la coyuntura.

Dicho con más sencillez, ya sea en la religión o en la guerra, seguimos órdenes. Seguimos los dictados no de nuestra conciencia sino de nuestras estructuras societarias. No se puede cuestionar a las religiones, ni dudar de ellas, del mismo modo que no se puede desafiar a los generales o a los reyes. Así que no es accidental que la guerra santa sea el escenario de una de las más impactantes historias de Conan. Podríamos fácilmente identificar a Conan con la E invertida de Lacan, que se usa en su gráfico de sexuación para representar al "único hombre no castrado". Obviamente, esto no significa que el joven bárbaro está rodeado de eunucos, sino más bien que sus aliados temporales se han insertado por completo en el orden simbólico; la castración, para Lacan, ocurre cuando nos insertamos por completo en el orden simbólico. Esta condición sine qua non para ser parte del mundo también significa obediencia, obediencia a la ley del padre, a las tradiciones de la sociedad y a los mandatos de la religión.

Todos en el ejército turanio creen en el sagrado Tarim, una figura mítica que los salvó de la ira del mar de Vilayet. Sus creencias son tan fuertes que a veces actúan como fanáticos irracionales, pero ¿no sucede esto con frecuencia incluso en el mundo de hoy? Desde los testigos de Jehová que no respetan tu privacidad y tocan con frecuencia la puerta de tu casa hasta un grupo de hombres capaces de secuestrar un avión porque están siguiendo órdenes divinas.

Todo lo que Conan ve es un ídolo de madera pintada reverenciado por todos, y por supuesto siente que esta guerra no merece esfuerzo alguno de su parte. A causa de esta herejía, Balthaz, el capitán de la nave, será su enemigo. Cuando el príncipe Yezdigerd explica que la guerra santa empezó cuando el Tarim encarnado fue robado de Turan y terminará solamente cuando sea recuperado y Makkalet sea destruida, él olvida mencionar una verdad más pedestre. Como señala Fafnir, Makkalet es el único rival para el comercio de Turan, así que la verdadera motivación aquí es, después de todo, asegurar las riquezas del reino exterminando a la competencia.

Del mismo modo que la religión influye en el comportamiento de la gente, la guerra tiene mecanismos similares. Como explica Slavoj Žižek "Los fundamentalistas hacen lo que ellos perciben como buenos actos para satisfacer la voluntad de dios y para ganar la salvación; los ateos hacen buenos actos simplemente porque es lo correcto, no lo hago para ganar el favor de dios; lo hago porque si no lo hiciera, no podría mirarme en el espejo. Un acto moral es por definición su propia recompensa. David Hume, creyente, resaltó esto de modo significativo cuando escribió que la única forma de mostrar verdadero respeto a dios es actuar moralmente ignorando la existencia de dios". En la vida real, la mayoría de creyentes depende enteramente de un gran Otro, una deidad que flota sobre sus cabezas y los vigila. La actitud heterónoma es bastante común incluso en el siglo XXI.

Al igual que la religión, la guerra también nutre la heteronomía del hombre. Del mismo modo que los oficiales nazi declaraban su inocencia al decir que "sólo seguían órdenes", los soldados son entrenados para hacer lo que se les dice, erradicando así todo rastro de autonomía. Ninguna guerra podría ocurrir si no fuera legitimada de algún modo. Así es que todas las guerras siguen ciertas narrativas predeterminadas que impiden que el hombre común -el soldado de a pie- descubra la verdad. Palabras como patriotismo y honor son parte del lenguaje de la guerra, pero no serían tan efectivas sin una estructura narrativa clara. ¿Cómo empezó la guerra entre Ilión y los aqueos? Podemos creer en el origen poético descrito por Homero y otros autores griegos (es decir, el rapto de la bella Helena a manos de Paris) o el hecho de que en el inicio del periodo micénico, Troya -a causa de su ubicación geográfica- era un rival natural para la supremacía marítima de los aqueos. ¿Cuál fue la motivación detrás de la conquista de América? De acuerdo a los reyes de España, había una imperiosa necesidad de evangelizar a todos en este nuevo continente, al llevar la palabra de dios a estos pueblos exóticos, España actuaba piadosamente. Los documentos reales enfatizan esta 'buena obra' pero, convenientemente, olvidan resaltar la inmensa cantidad de oro obtenida de los incas y otras civilizaciones. ¿Cuál fue la justificación de la guerra de Irak? Armas letales, arsenal nuclear, etc., la verdad sin embargo se hizo evidente: las compañías petroleras y la industria de armamento obtuvieron fuertes ganancias con esta guerra. Así que para cada guerra hay una justificación, una historia que pertenece a la realidad, pero si tenemos una mente crítica descubriremos lo 'real' que subyace a todo esto.

Conan y Fafnir son capaces de entender las intenciones de los hombres de Turan, pero ya no hay vuelta atrás. Y sin mucha convicción, el cimerio y el vanir atacan la costa de Makkalet. He leído este cómic muchas veces en mi vida. Es difícil imaginar una mejor manera de describir una guerra a gran escala que enfocándose en dos extranjeros, dos hombres que tienen otros dioses y otras actitudes. En un sólo ejemplar, Roy Thomas proporciona una análisis profundo de la guerra y la religión, con una complejidad y madurez que son imposibles de encontrar 40 años después (dentro y fuera de la industria del cómic). De hecho, por paradójico que suene, en épocas recientes la inmadurez se ha convertido en la norma para la religión (apenas hace un par de años los norteamericanos insistían en que el creacionismo se enseñe en los colegios y los musulmanes amenazaban con bombardear ciudades a causa de una caricatura de Mohammed).

No obstante, este número de Conan el bárbaro no sería igual sin el hermoso arte de Barry Windsor-Smith. La primera página retrata a un Conan meditabundo, hay una sensación de gravedad, los lápices y las tintas logran otorgarle peso de verdad. Conan está sentado con una expresión sombría, como si fuera la famosa estatua esculpida por Auguste Rodin "El pensador", que fue llamada así erróneamente ya que Rodin de hecho la concibió como "Dante en las puertas del infierno". Ese es el sentimiento que expresa Conan, él intuye el infierno que se avecina. Porque, como Sartre dijo tan acertadamente “l'enfer, c'est les autres” (el infierno son los otros).

La segunda página que incluyo aquí es un recuento de los logros del Tarim, este mito fundacional que recrea la figura del mesías, presente en tantas religiones. Luego tenemos una extraordinaria secuencia compuesta por viñetas altas y angostas, mientras Conan camina hacia una gaviota. La paz de la escena contrasta con los pensamientos del joven bárbaro: "Aquí entre hombres llamados civilizados, un extraño puede sonreír y extender una mano... mientras la otra se cierne furtivamente sobre la daga oculta. Aquí Conan encuentra insondables todos los motivos... y arteras todas las acciones...". El primer vistazo a la flota de asedio de Turan es también una escena poderosa, tiene la misma seriedad que los grabados de Durero. La ciudad de Makkalet es una joya arquitectónica. Barry Windsor-Smith construye esta ciudad piedra por piedra, en una época la que no existían las imágenes generadas en computadoras; hoy en día, un software como sketch-up impide que los artistas hagan el trabajo pesado y dibujen una simple pared o un par de ventanas. La caída de Fafnir y el desenlace final de la batalla son ejemplos indiscutibles del talento del artista británico. Y el próximo número es todavía mejor.

March 25, 2012

Winter Soldier # 1 - Ed Brubaker & Butch Guice

|

| Lee Bermejo |

So I was a bit on the fence when I saw the solicitations for Winter Soldier. But Lee Bermejo’s cover was quite persuasive. And so I preordered it. I read it. And I enjoyed it. Brubaker returns to that which he does best: spies, intrigues and crime with a noir feel. And Butch Guice is the ideal artistic partner for such a project. I must admit that since page one I felt immediately seduced by Guice’s wonderful art. His pages in Captain America were great, but I think he’s even greater here.

Guice has graphically rechanneled the tradition of Marvel’s espionage books of the past, and thus, we have a certain sense of Jim Steranko’s Nick Fury in these pages. Just the thought of having 9 panels in a single page (quite a striking page, by the way) is like a revolutionary statement nowadays, in an era which artists seem quite comfortable with several splash pages and double page spreads per issue. The layout of the panels and the grittiness of Guice’s inks converge in a magnificent visual treat.

|

| Butch Guice |

Winter Soldier does feel like a very nice homage to the comics of the past, with an outstanding artistic approach and a very solid script. Someone could ask, however, what is the relevance of Russian spies in the 21st century? Well, as Slavoj Žižek wrote recently “we no longer have wars in the old sense of a conflict between sovereign states in which certain rules apply”. This, of course, finds a special validation if the course of Winter Soldier’s first issue, in which James “Bucky” Barnes remembers that during the Cold War, one skillful agent, in the right time and the right place, could be more effective than an army. Ivan Kragoff (also known as the villainous Red Ghost) subscribes to this idea too, which is in itself quite logical since in today’s world one terrorist, given the opportunity, can be more harmful than an entire army.

|

| 9 amazing panels / 9 viñetas asombrosas |

Why did Bucky Barnes replace Captain America a couple of years ago? Steve Rogers, the idealistic and noble hero had died trying to protect innocent lives in the aftermath of Civil War. But this was also a symbolic death that had a clear statement: America, as we knew it, was gone. Or, at least, there had been some profound changes, and that is why Bucky, as the new Captain America, could do things that Steve Rogers would not even consider. Aided by Natasha Romanov (AKA the Black Widow), Winter Soldier faces a dangerous threat and unknown enemies in this new title, enemies that have decided to attack the embassy of Latveria. The target? Doctor Doom.

Certainly, what I referred to as “change” can be exemplified not only by Bush’s Patriotic Act but also by Jonathan Alter’s Newsweek article ‘Time to Think about Torture’; here, an average American citizen, in the end, arrives to a debatable conclusion: “It’s a new world, and survival may well require old techniques that seemed out of the question”.

One of the things that I enjoyed the most before the return of Steve Rogers was the constant questioning in Bucky’s mind. He knew he had resorted to all these ‘old techniques’, he knew that as the Winter Soldier he had killed and tortured many people, and yet he was now using the mantle of America’s most beloved hero. These internal contradictions transformed Bucky into a multidimensional character that had nothing to do with his more naïve and childish iteration from the 40s. Here’s hoping that Brubaker and Guice will take us again into a similar path of enjoyment.

_______________________________________________________________________________________

|

| Winter Soldier & Black Widow |

Leí el inicio de la nueva etapa del Capitán América el año pasado y no me sentí particularmente interesado. No es que Ed Brubaker escribiese un relato pobre, sino que no sentí ninguna urgencia en saber qué pasaría a continuación. He tenido algunos problemas con Brubaker en el pasado, su primer arco en Daredevil fue intenso e inolvidable, pero después algunos de sus recursos narrativos se sentían como estancados, monótonos.

Así que cuando me enteré de que saldría Winter Soldier dudé. Pero la portada de Lee Bermejo fue bastante persuasiva. Así que hice mi compra por adelantado. Lo leí. Y lo disfruté. Brubaker regresa a lo que mejor sabe hacer: espías, intrigas y crimen con un aire a serie negra. Y Butch Guice es el aliado artístico ideal para semejante proyecto. Debo admitir que desde la primera página me sentí inmediatamente seducido por el maravilloso arte de Guice. Sus páginas en Capitán América eran muy buenas, pero creo que aquí son incluso mejores.

Guice ha canalizado la tradición de los títulos de espionaje de Marvel de antaño, y de este modo, tenemos páginas que nos recuerdan al Nick Fury de Jim Steranko. Sólo la idea de tener 9 viñetas en una sola página (preciosa página, por cierto) parece revolucionario en la actualidad, en una etapa en la que los artistas se sienten más cómodos mientras menos tengan menos viñetas que elaborar. La distribución de los paneles y la determinación de las tintas de Guice convergen en un magnífico festín visual.

|

| Doctor Doom |

Winter Soldier es un óptimo homenaje a los cómics del pasado, con un estupendo enfoque artístico y un guión muy sólido. Alguien podría preguntar, sin embargo, ¿qué relevancia tienen los espías rusos en el siglo XXI? Bueno, como escribió Slavoj Žižek hace poco "ya no hay guerras en el viejo sentido de un conflicto entre estados soberanos en donde se aplican ciertas reglas". Esto, por supuesto, es especialmente válido en el transcurso del primer número de Winter Soldier, en el que James “Bucky” Barnes recuerda que durante la Guerra Fría, un agente capaz, en el lugar y en el momento adecuado, podía ser más más efectivo que un ejército. Ivan Kragoff (también conocido como el villano Red Ghost) piensa exactamente lo mismo, que no deja de ser bastante lógico, y es que en el mundo de hoy un terrorista, si tiene la oportunidad, puede causar más daño que todo un ejército.

¿Por qué Bucky Barnes reemplazó al Capitán América hace un par de años? Steve Rogers, el héroe noble e idealista había muerto intentando proteger vidas inocentes en el desenlace de Civil War. Pero esta fue también una muerte simbólica que tenía un significado: Estados Unidos, como lo conocíamos, ya no existía. O, por lo menos, habían ocurrido profundos cambios, y es por ello que Bucky, como el nuevo Capitán América, podía hacer cosas que Steve Rogers ni siquiera consideraría. Ayudado por Natasha Romanov (Black Widow), Winter Soldier se enfrenta a una peligrosa amenaza y a enemigos desconocidos en esta nueva colección, enemigos que han decidido atacar la embajada de Latveria. ¿El objetivo? Doctor Doom.

Ciertamente, el 'cambio' al que me refería puede ser ejemplificado no sólo por el Acta Patriótica de Bush sino también por el artículo de Newsweek de Jonathan Alter "Es momento de pensar en la tortura"; aquí, un típico ciudadano norteamericano llega a una debatible conclusión: "Es un nuevo mundo, y la sobrevivencia puede requerir viejas técnicas que antes no habríamos considerado".

Una de las cosas que más disfruté antes del regreso de Steve Rogers fue el constante cuestionamiento interno de Bucky. Él sabía que había recurrido a todas estas 'viejas técnicas', él sabía que, como Winter Soldier, había asesinado y torturado a mucha gente, y no obstante estaba usando el manto del héroe más amado de Estados Unidos. Estas contradicciones internas transformaron a Bucky en un personaje multidimensional que no tenía nada que ver con su versión más inocente e infantil de los años 40. Espero que Brubaker y Guice no se aparten del buen camino.

March 23, 2012

Severed # 7 - Snyder, Tuft & Attila Futaki

Scott Snyder and Scott Tuft have created an engrossing tale about horror and childhood, about the level of poverty in the 20s (id est, the failure of society) and the search of the father (id est, the nom de pere, the one and final instance that helps us make sense of the world). When Jack Garron run away from his mother in a futile attempt to find his father, he almost got raped in a train, he befriended a cross-dressing girl named Sam, and eventually decided to trust in an old and sinister salesman with a special hunger for innocent flesh.

Imbricated amidst the poverty and the famine of rural America, we have the presence of this incarnation of evil, this traveling salesman that eats the bodies of children. Cannibalism here, understood as the act of eating a member of our own species, mirrors the reality of the world in which 12-year-old Jack lives. What is America during the depression if not a big, wounded animal that tries to devour itself hoping to placate a hunger that had never been experienced before?

Cannibalism is often associated with wilderness, with the lack of law. There is an old joke about an explorer that finds a tribe of savage men and asks them if they’re cannibals, the answer is quite revealing: “No, there aren’t any more cannibals in our region. Yesterday, we ate the last one”. According to them, there are no more cannibals, but the subject of enunciation proves that cannibalism exists.

The mysterious salesman has always acted like a predator that hides under false subterfuges, such as the joke mentioned above. According to Kant, this exemplifies “the intrusion of the ‘subject of enunciation’ of law: this obscene agent who ate the last cannibal in order to ensure the order of the law”. Hegel later on found out that law and duty would always have an obscene side, like the reverse of a coin. Thus the salesman obeys his own law so faithfully and compulsively that he is, indeed, the obscene side of the law. He is the man that will get rid of cannibals by eating them.

Now that Jack is tied up and defenseless, the salesman explains to him that he enjoys eating children with dreams. He hunts them down, gives them a glimpse of whatever it is they desire, and then butchers them to pieces. Much can be said about cannibalism and its connection with America in the 20s, and all of this could be imbricated in the ever illusive parental figure that fuels Jack’s dreams. But I don’t want to spoil this last issue to anyone. Suffice to say that the horror is present from page one to the last.

Of course, if the salesman looks horrifying to us it is because of Attila Futaki’s art. I have commented several times the enormous talent of this artist, but in the pages of the final issue of Severed, Attila is even greater than usual. The darkness of Jack’s imprisonment is quite intense here, the final confrontation between a wounded and armless Jack and the salesman are beautiful and yet terrifying at the same time. This is the final issue of an amazing miniseries, if you haven’t read it yet, you still have the chance to buy the hardcover. I urge you to do it.

And my other reviews:

Severed # 1, Severed # 2, Severed # 3, Severed # 4, Severed # 5 & Severed # 6

____________________________________

Scott Snyder y Scott Tuft han creado un cautivador relato sobre el horror y la infancia, sobre el nivel de pobreza de los 20 (es decir, el fracaso de la sociedad) y la búsqueda del padre (es decir, el nom de pere, la instancia final que nos ayuda a darle sentido al mundo). Cuando Jack Garron huyó de su madre en un fútil intento de encontrar a su padre, casi sufre una violación en un tren, entabló amistad con una chica que asumía una identidad masculina y eventualmente confió en un viejo y siniestro vendedor con un apetito por la carne inocente.

Imbricada en la pobreza y el hambre de la Norteamérica rural, tenemos la presencia de esta encarnación del mal, este vendedor viajante que come cuerpos de niños. El canibalismo, aquí, es entendido como el acto de devorar a un miembro de nuestra propia especie, y refleja la realidad del mundo en el que vive Jack, un niño de 12 años. ¿Qué es Estados Unidos durante la depresión si no un gran animal herido que trata de devorarse a sí mismo esperando aplacar el hambre que nunca antes había experimentado?

El canibalismo es asociado a menudo con lo salvaje, con la ausencia de ley. Hay una vieja broma sobre un explorador que encuentra una tribu de salvajes y les pregunta si son caníbales, la respuesta es claramente reveladora: "No, ya no hay caníbales en nuestra región. Ayer, nos comimos al último". Según ellos, no hay más caníbales, pero el sujeto de enunciación demuestra que el canibalismo existe.

El misterioso vendedor siempre ha actuado como un depredador que se esconde bajo falsos subterfugios, como la broma que he mencionado. De acuerdo a Kant, esto ejemplifica "la intrusión del 'sujeto de enunciación' de la ley: este agente obsceno que se comió al último caníbal para asegurar el cumplimiento de la ley". Hegel luego diría que la ley y el deber siempre tendrán un lado obsceno, como el reverso de la moneda. Por lo tanto, el vendedor obedece su propia ley tan compulsiva y fielmente que él es, de hecho, el lado obsceno de la ley. Él es el hombre que elimina a los caníbales comiéndoselos.

Ahora que Jack está atado e indefenso, el vendedor le explica que disfruta comiéndose a niños soñadores. Los caza, les permite atisbar aquello que desean, y luego los masacra, los hace pedazos. Se podría decir mucho sobre el canibalismo y su conexión con los Estados Unidos en los años 20, y todo esto podría imbricarse en la figura paterna eternamente elusiva que alimenta los sueños de Jack. Pero no quisiera arruinar las sorpresas de este último número. Basta decir que el terror está presente desde la primera hasta la última página.

Por supuesto, si el viajante se ve terrorífico es gracias al arte de Attila Futaki. He comentado diversas veces el enorme talento del artista, pero en estas páginas finales, Attila está incluso mejor que al inicio. La oscuridad que aprisiona a Jack es bastante intensa, la confrontación final entre Jack herido -y sin un brazo- y el vendedor es bella y aterrorizante a la vez. Este es el último número de una asombrosa miniserie, si no la han leído, todavía tienen la oportunidad de comprar el tomo recopilatorio, y deberían hacerlo.

Y mis otras reseñas:

Severed # 1, Severed # 2, Severed # 3, Severed # 4, Severed # 5 & Severed # 6

Imbricated amidst the poverty and the famine of rural America, we have the presence of this incarnation of evil, this traveling salesman that eats the bodies of children. Cannibalism here, understood as the act of eating a member of our own species, mirrors the reality of the world in which 12-year-old Jack lives. What is America during the depression if not a big, wounded animal that tries to devour itself hoping to placate a hunger that had never been experienced before?

|

| Attila Futaki |

Cannibalism is often associated with wilderness, with the lack of law. There is an old joke about an explorer that finds a tribe of savage men and asks them if they’re cannibals, the answer is quite revealing: “No, there aren’t any more cannibals in our region. Yesterday, we ate the last one”. According to them, there are no more cannibals, but the subject of enunciation proves that cannibalism exists.

The mysterious salesman has always acted like a predator that hides under false subterfuges, such as the joke mentioned above. According to Kant, this exemplifies “the intrusion of the ‘subject of enunciation’ of law: this obscene agent who ate the last cannibal in order to ensure the order of the law”. Hegel later on found out that law and duty would always have an obscene side, like the reverse of a coin. Thus the salesman obeys his own law so faithfully and compulsively that he is, indeed, the obscene side of the law. He is the man that will get rid of cannibals by eating them.

Now that Jack is tied up and defenseless, the salesman explains to him that he enjoys eating children with dreams. He hunts them down, gives them a glimpse of whatever it is they desire, and then butchers them to pieces. Much can be said about cannibalism and its connection with America in the 20s, and all of this could be imbricated in the ever illusive parental figure that fuels Jack’s dreams. But I don’t want to spoil this last issue to anyone. Suffice to say that the horror is present from page one to the last.

Of course, if the salesman looks horrifying to us it is because of Attila Futaki’s art. I have commented several times the enormous talent of this artist, but in the pages of the final issue of Severed, Attila is even greater than usual. The darkness of Jack’s imprisonment is quite intense here, the final confrontation between a wounded and armless Jack and the salesman are beautiful and yet terrifying at the same time. This is the final issue of an amazing miniseries, if you haven’t read it yet, you still have the chance to buy the hardcover. I urge you to do it.

And my other reviews:

Severed # 1, Severed # 2, Severed # 3, Severed # 4, Severed # 5 & Severed # 6

____________________________________

|

| Jack loses an arm / Jack pierde un brazo |

Scott Snyder y Scott Tuft han creado un cautivador relato sobre el horror y la infancia, sobre el nivel de pobreza de los 20 (es decir, el fracaso de la sociedad) y la búsqueda del padre (es decir, el nom de pere, la instancia final que nos ayuda a darle sentido al mundo). Cuando Jack Garron huyó de su madre en un fútil intento de encontrar a su padre, casi sufre una violación en un tren, entabló amistad con una chica que asumía una identidad masculina y eventualmente confió en un viejo y siniestro vendedor con un apetito por la carne inocente.

Imbricada en la pobreza y el hambre de la Norteamérica rural, tenemos la presencia de esta encarnación del mal, este vendedor viajante que come cuerpos de niños. El canibalismo, aquí, es entendido como el acto de devorar a un miembro de nuestra propia especie, y refleja la realidad del mundo en el que vive Jack, un niño de 12 años. ¿Qué es Estados Unidos durante la depresión si no un gran animal herido que trata de devorarse a sí mismo esperando aplacar el hambre que nunca antes había experimentado?

|

| final confrontation / la confrontación final |

El canibalismo es asociado a menudo con lo salvaje, con la ausencia de ley. Hay una vieja broma sobre un explorador que encuentra una tribu de salvajes y les pregunta si son caníbales, la respuesta es claramente reveladora: "No, ya no hay caníbales en nuestra región. Ayer, nos comimos al último". Según ellos, no hay más caníbales, pero el sujeto de enunciación demuestra que el canibalismo existe.

El misterioso vendedor siempre ha actuado como un depredador que se esconde bajo falsos subterfugios, como la broma que he mencionado. De acuerdo a Kant, esto ejemplifica "la intrusión del 'sujeto de enunciación' de la ley: este agente obsceno que se comió al último caníbal para asegurar el cumplimiento de la ley". Hegel luego diría que la ley y el deber siempre tendrán un lado obsceno, como el reverso de la moneda. Por lo tanto, el vendedor obedece su propia ley tan compulsiva y fielmente que él es, de hecho, el lado obsceno de la ley. Él es el hombre que elimina a los caníbales comiéndoselos.

Ahora que Jack está atado e indefenso, el vendedor le explica que disfruta comiéndose a niños soñadores. Los caza, les permite atisbar aquello que desean, y luego los masacra, los hace pedazos. Se podría decir mucho sobre el canibalismo y su conexión con los Estados Unidos en los años 20, y todo esto podría imbricarse en la figura paterna eternamente elusiva que alimenta los sueños de Jack. Pero no quisiera arruinar las sorpresas de este último número. Basta decir que el terror está presente desde la primera hasta la última página.

Por supuesto, si el viajante se ve terrorífico es gracias al arte de Attila Futaki. He comentado diversas veces el enorme talento del artista, pero en estas páginas finales, Attila está incluso mejor que al inicio. La oscuridad que aprisiona a Jack es bastante intensa, la confrontación final entre Jack herido -y sin un brazo- y el vendedor es bella y aterrorizante a la vez. Este es el último número de una asombrosa miniserie, si no la han leído, todavía tienen la oportunidad de comprar el tomo recopilatorio, y deberían hacerlo.

Y mis otras reseñas:

Severed # 1, Severed # 2, Severed # 3, Severed # 4, Severed # 5 & Severed # 6

March 22, 2012

No Place Like Home # 1 - Angelo Tirotto & Richard Jordan

Horror appeals to me in so many different levels. Unlike other people, I find horror movies -or comic books- as fascinating, if not more, than the pseudo-intellectual academic rubbish I was forced to read before majoring in Literature. So whenever I come across something horror-related, I give it a try. I simply can’t help it.

How does this new horror title from Image Comics begin? After five years, Dee returns to Kansas, to her parents’ funeral. They died after a hurricane destroyed their house, or so she has been told. But whatever has happened to her parents had happened before, decades ago. And now it’s happening again.

Angelo Tirotto, inspired by L. Frank Baum and the Wizard of Oz, uses elements that are quite familiar to us but at the same time introduces enough mystery and intrigue to keep us at the edge of our seats. Dee has returned to her origins, to her past. Home is what she knows, and it still looks and feels very much like usual. Except that we know that truth is not knowledge. Truth is rather what makes knowledge stumble. At times truth has been incarnated in the history of mankind, by the child, by the woman, by the outcast; from their supposed ignorance comes a truth which disorganizes those who know. The outcast here is the ‘town drunk’, the only man who knows the truth and is willing to disorganize those who know, or think they know, the real cause of the demise of Dee’s parents.

Knowledge depends on language and articulation, and apparently consistency fixed by the master signifier. Dee’s old friends and relatives talk to her serenely, calmly. To speak the truth is always to accept inconsistency. But after yet another gruesome death in town, Dee perhaps will understand that in order for her to survive she must first find the truth, even if that means disarticulating knowledge… everything you know can be a lie, after all.

Richard Jordan’s pages are quite exquisite, and since I had never read anything from Tirotto before “No place like home” it was the art which sold me on this. I’m glad I preordered the first issue. I like the way Richard’s characters look real, they’re very down-to-Earth people after all; this artist has clearly found his style, and he has a special quality that you recognize in every page. A really promising start.

____________________________________________________________________________________

El terror me interesa por muchos motivos. A diferencia de otras personas, encuentro las películas o cómics de terror tan o más fascinantes que toda la quincalla pseudo-intelectual que he tenido que leer en la facultad de literatura. Así que cada vez que veo algo de terror, mi interés se aviva. No lo puedo evitar.

¿Cómo empieza este nuevo título de terror de Image Comics? Después de 5 años, Dee regresa a Kansas, al funeral de sus padres. Ellos murieron cuando un huracán destrozó su hogar, o eso es lo que se dice. Pero lo que le pasó a sus padres ya ha ocurrido antes, hace décadas, y ahora está sucediendo de nuevo.